Research continues into the life of Dido Elizabeth Belle, daughter of Sir John Lindsay, yet to date only a limited amount of information is widely known today about the life of his other surviving illegitimate daughter, and half-sister to Dido, named Elizabeth (known as Eliza) Lindsay aka Palmer, as to a large extent she seems to have been written out of history. However, it would be Elizabeth and her half-brother John, whose existence Sir John acknowledged in his will as his ‘reputed’ children.

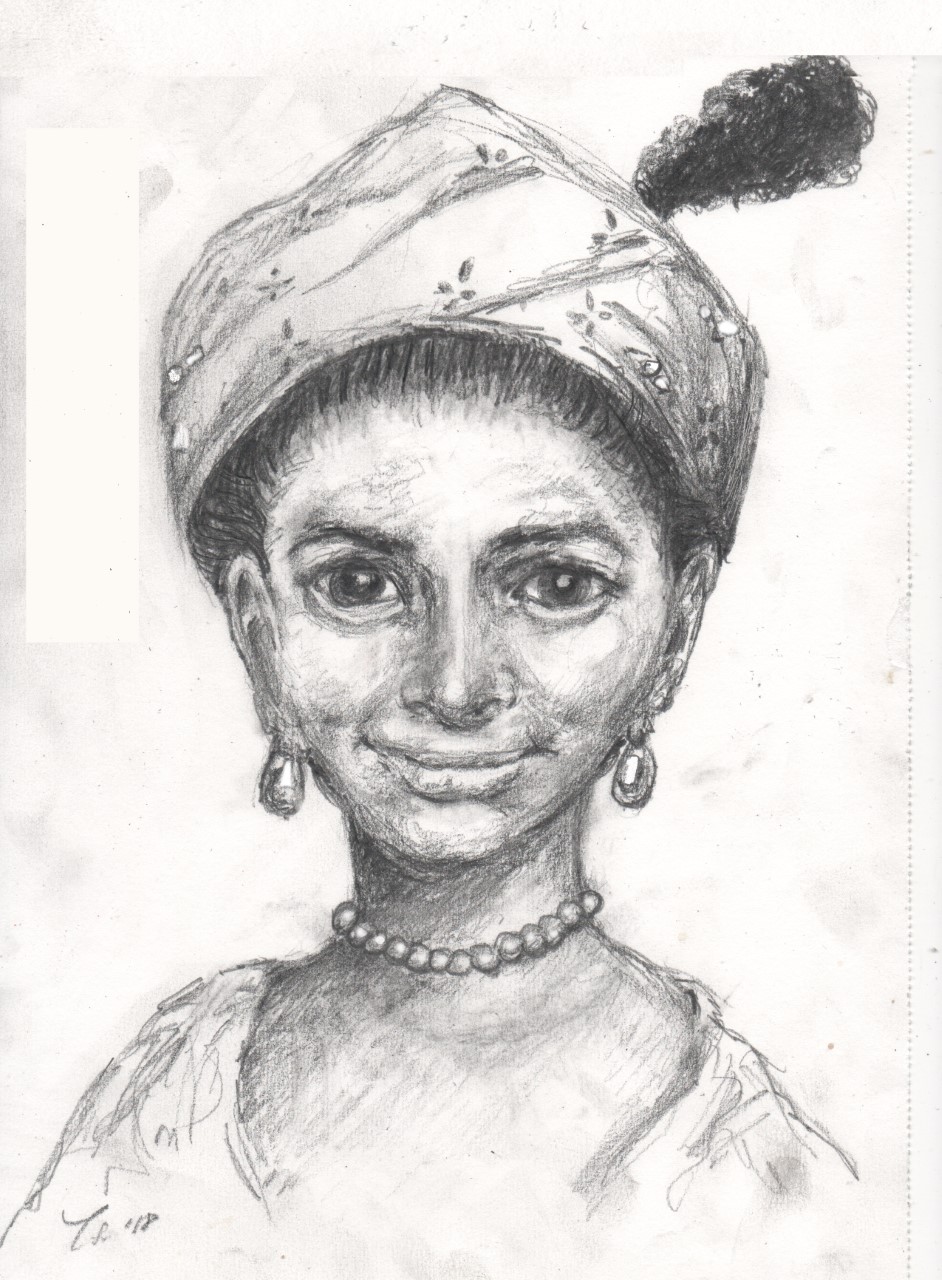

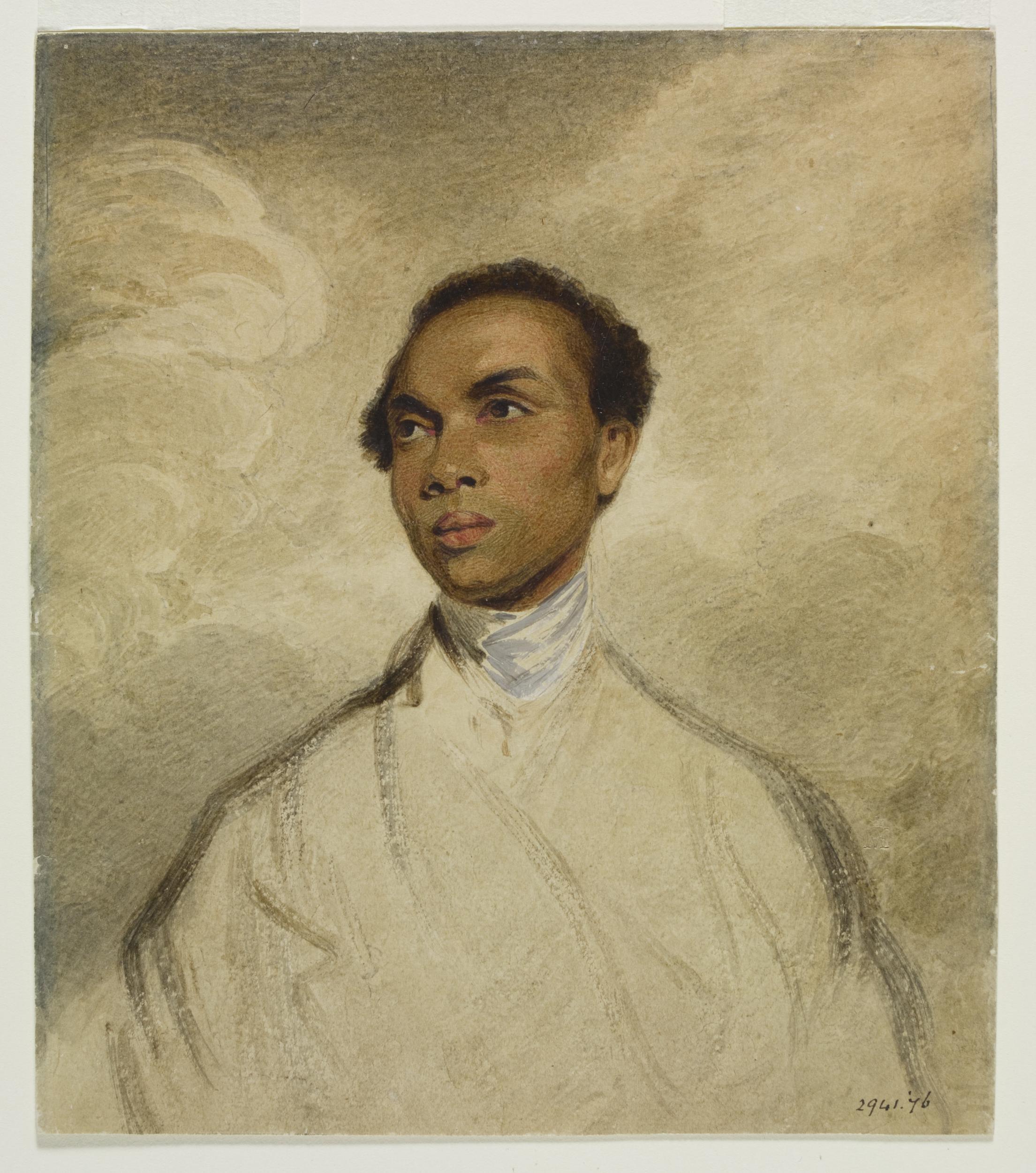

With that, let me introduce you to Peter Hill and Mr Elizabeth Hill née Lindsay or Palmer. Sadly, we don’t know the artist of these paintings.

Much research has been quietly carried out by Eliza’s descendants, especially Christopher Normand, and it’s thanks to his generosity in sharing the information he gleaned, along with the photograph of Eliza and her husband, which has allowed me to delve deeper into her life and her family.

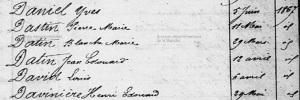

Eliza was born 8 December 1766 in Jamaica, just a few days after Dido was being baptised on the other side of the world, in London. As we see here from her baptism at Port Royal, Jamaica, it took place when she was a month old, on 10 January 1767.

Her baptismal record shows quite clearly, Sir John Lindsay as being her father, which he appears to have acknowledged throughout her life. Her mother was simply named as Martha G and there is nothing on the baptismal entry to tell us more about Eliza’s mother, but the majority of baptisms at that time record ethnicity if non white, and as can be seen above, there is nothing against either Eliza or her mother’s name, which in all likelihood means that unlike Dido, Eliza was white.

It remains unclear as to when Eliza and her half-brother, John, who was born in November 1767 arrived in Britain.

Presumably Sir John felt the pair would have better life chances here rather than remaining in Jamaica and in Britain under Sir John’s care, they would receive a good education.

It seems highly likely that Eliza and possibly John, were raised in Edinburgh, meaning they would be close to Sir John’s mother, Lady Amelia Lindsay (1691-1774) and his sister, Lady Katherine Henderland (1737-1828), the wife of Judge Alexander Murray, Lord Henderland (1736-1795).

It was in September 1768 that Eliza’s father married Mary Milner, a name we will return to later in Eliza’s life.

Little is known of Eliza’s early life, but it has been suggested by her descendants that she attended a boarding school in Edinburgh, which I do agree with, especially in light of a reference that appeared in the accounts of John Lindsay junior, who noted that a woman by the name of Mrs Murray was to be paid for the education and board of a Miss Eliza Lindsay.

Whilst I am not sure whether this related to this his sister, Eliza or whether it pertained to his own daughter, whose name has not yet come into view, it is certainly of interest.

This question left me wondering whether there was any record of boarding schools around Edinburgh at the time Eliza would have been educated when I came across a document which included a Mrs Katherine Murray, who ran a boarding school from 1756, at Niddry’s Wynd. Niddry’s Wynd being fairly close to where Eliza was married, so it seems feasible, although I have no proof especially given this Mrs Murray ran the school in the latter part of the 1750’s that she was still there when Eliza attended, but it’s an interesting theory for now.

Around 1772, Eliza’s future husband, Peter Hill became apprenticed to Mr William Creech, a publisher and bookseller at that time. Edinburgh was renowned for its booksellers and Creech was arguably one of the most famous, so much so that the area around his shop became known as Creech’s Land.

Creech published for many authors such as the poet, Robert Burns, and also Dr James Beattie, who met Dido Elizabeth Belle at Kenwood House in 1771, which begs the question as to whether Beattie ever knew that the then young Peter Hill went on to marry Sir John Lindsay’s other daughter, Eliza. It was a small world at that time where anyone who was anyone knew each other, although Eliza would only have been a young child at the time, as there was an eleven year age gap between Eliza and Peter Hill.

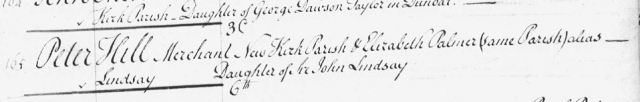

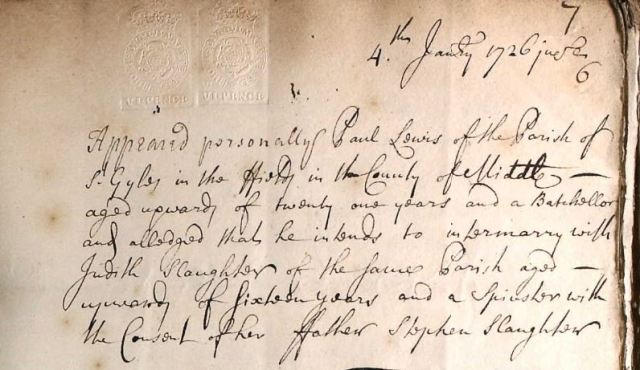

Eliza and Peter married in Edinburgh on 3 May 1783, Eliza was 16 at the time and the marriage entry recorded her name as Elizabeth Palmer, alias Lindsay, daughter of Sir John Lindsay. Despite many attempts it has not been possible to ascertain why she used the name Palmer, unless it was in honour of someone who raised her.

On 29 September that year, Sir John wrote his will, in which he made provision of £1,000 each for John and Eliza, which was to be left in a trust, to be administered by his wife, Dame Mary Lindsay.

Now, it’s worth noting that Sir John named his daughter, Elizabeth Lindsay i.e. he used her maiden name, which arguably implies that he was unaware that Eliza had been married for 4 months by then, which could possibly tie in with the theory that the couple eloped, especially given Eliza’s age.

When they first married they are believed to have rented a flat at the head of The Mound, Edinburgh.

It would be just over a year into their marriage that their first child, Amelia was born, presumably named for her paternal grandmother, which seems to imply that she either knew or knew of her grandmother.

It is interesting to note that Eliza gave her maiden name on her daughter’s baptism, Palmer and not Lindsay, as she would go on to do for all her children, for some unexplained reason. Within the following year, they moved from The Mound to a property at 160 Nicolson Street on the corner of Hill Place. It has been suggested that Hill Place was named after Peter, however it was named after James Hill, a mason who was involved in building many houses in that area.

It seems highly likely that it was around this time, that William Creech and Peter had gone their separate ways, with Peter establishing his own bookshop. The Female Servant Tax Rolls of 1785, shows that Peter and Eliza had moved to Nicolson Street and were employing a servant, Mary Sherry.

In March 1786, Eliza and Peter’s second child entered the world, another girl, Margaret. Then shortly after this they moved again, this time to Parliament Close, as Peter’s name appeared in the shop rates 1788/89.

It was in 1787 that Peter and Eliza first became acquainted with the poet, Robert Burns who would become a regular visitor and correspondent. Eliza was said to have been Peter’s superior, socially and is believed to have disapproved of her husband’s acquaintance with the poet. However, Burns described Eliza as ‘my fair friend’ and clearly enjoyed her company.

February 1788, Peter took on an apprentice, Archibald Constable, who lived in with the family. Constable would later write:

Mr Hill had been for many years principal clerk to Mr Creech, was highly respected as possessing gentlemanly manners beyond most others of the trade and proved in this year and important stage of my career a kind and indulgent master.

Constable went on to say:

I lived in the house with him … I passed six years very happily as an apprentice, and another as a clerk, receiving in the last year £30 of salary. Mr Hill’s shop was frequented by the most respectable persons in Edinburgh. Burns the poet when in town was a frequent visitor, the distinguished professors and clergy, and the most remarkable strangers. I remember Captain Gross making frequent visits …

Mr Hill did not remain long in the Parliament Close, but removed about the year of 1790 to the shop at the cross where he now is, his apprentices, clerks and shopmen increasing with his trade, which was very considerable.

NB Captain Gross (sic) was Francis Grose, the well-known author of A Classical Dictionary of the Vulgar Tongue.

Another of Peter’s employees was the mathematician an astronomer, William Wallace, who joined Peter towards the latter part of Archibald’s apprenticeship.

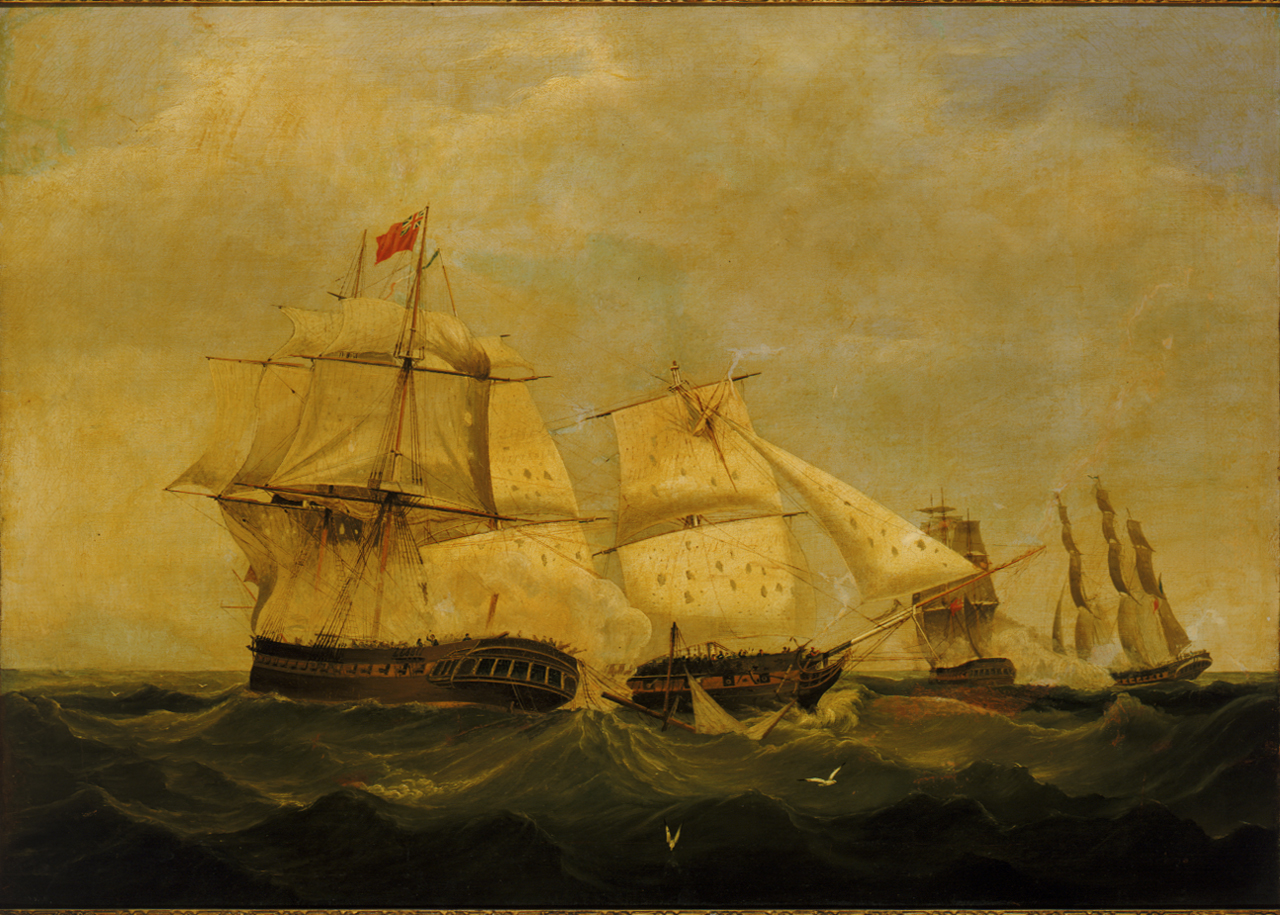

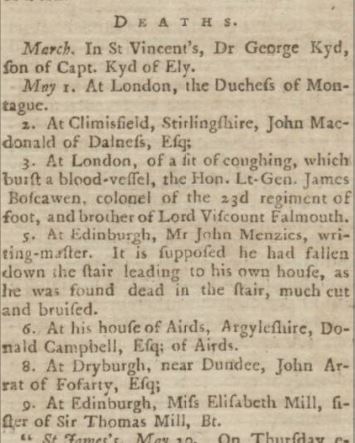

In June 1788, Eliza’s father, Sir John Lindsay died, as to when Eliza found out of her father’s death remains unanswered, but it would have been from this point onwards that she would have begun to receive the £1,000 left to her in his will. £1,000 was not an insignificant sum of money at that time and would equate to around £120,000 in today’s money (Bank of England). The same amount was also left to her brother, John.

Business appeared to be going well for Peter, and he and his family continued to move, presumably to bigger and better premises, this move took them to James’s Court, but in their domestic life tragedy struck again, in March 1789 when their four year old daughter, Amelia died from a fever.

Around this time, Eliza had two further children, John and James, both presumably named for Eliza’s and Peter’s fathers, although to date I have found no record of their births or deaths, but in 1790 the Servant Tax return confirms that they had two servants and 3 children, these children would have been, Margaret, James and John.

On 2 March 1790, Peter received a letter from Robert Burns, which included the following about Eliza:

And now, to quit the dry walk of business, how do you do my dear friend? and how is Mrs. Hill? I trust, if now and then not so elegantly handsome, at least as amiable, and sings as divinely as ever.

11 May 1791 saw the baptism of Elizabeth’s first son who would survive infancy and named Peter, for his father.

Here we see Peter (senior) paying tax in 1791-2 for owning a horse and carriage:

As if any further proof were needed that Eliza was Sir John’s daughter, around 1793 Eliza had another daughter, whom she very clearly named after her step-mother – Mary Milner, it would appear crystal clear from this naming that she knew and respected her stepmother. I would argue that there was a much closer relationship, despite the distance, between Eliza and her father’s side of the family. At this time, the family moved again, this time to a house on Ramsay Gardens, Edinburgh.

Between 1793 and 1798 trials for sedition were held in Edinburgh, with Eliza’s uncle, Alexander Murray, Lord Henderson being one of the leading judges in the trials. When you look at the case of one of these men, Joseph Gerrald, another name comes into view, that of Peter Hill. It transpires that Peter was the Clerk, and therefore, Eliza would be well aware of these court cases.

In March 1794, Sir John Lindsay’s wife, Dame Mary wrote her will, in which she ensured Sir John two ‘reputed’ children continued to receive their inheritance from their father, although by this time Eliza had received £500 of the £1,000 trust. Dame Mary put in provision that upon her death the money should be paid to his children via Sir John’s sister, Katherine Murray, Lady Henderland. In addition to this, she personally left them £100 each (about £10.5k in today’s money). The same year, Peter’s name appeared in the Edinburgh Burgesses and Guild Brethren.

Around 1796, Eliza was pregnant again, this child was again believed to have been named John, but again, it seems likely he died shortly after birth; therefore no baptism or burial record has survived. The following year, 1797 their second surviving son, Alexander was born, with another daughter, Eliza being born just a year later. At this time, Peter was a member of the Edinburgh Council.

23 November 1799 Dame Mary Lindsay died, so at this time Eliza and her brother would have received their £100 legacy from their stepmother, money which would no doubt have been very welcome with a growing family, especially as Eliza had another daughter, Helen in 1800, closely followed in April 1802 by William Simpson.

In 1801 Peter had a catalogue published listing all the books he sold, in which he gave two addresses from where they may be purchase – his shop at The Cross, Edinburgh and this entry also tells us that he had a warehouse too, at Royal Bank Close, Edinburgh.

Sadly though 1803 would be a difficult year, with two of their children dying within days of each other. Alexander, by that time aged 5, died from water on the brain on 1 April 1803. Then on 14 April, William Simpson also died, no cause of death given for him though. This would have been especially difficult as Eliza who would have been heavily pregnant with their next daughter, named Lindsay, in honour of her father and also her maiden name. Lindsay was born on 10 Jul 1803.

21 October 1806, saw the birth of yet another child, their 14th child, a son, Francis Bridges, who lived until the age of 20, when he died from ‘decline’ in 1826. They were reputed to have had a 15th child, Robert in 1810, but there is no evidence of this child, if he existed, having survived infancy.

By 1805 Peter was no longer a bookseller and had become the city treasurer and in 1809 he was also the treasurer of George Heriot’s Hospital, a post he held until 1813 when he became the Chief Collector of Burgal Taxes.

At the end of January 1821 Eliza’s brother, John died in India. Like their stepmother, John didn’t forget his sister in his will. He left a legacy for Eliza and also wrote off debt of £300 which her husband owed him, although John didn’t elaborate as to what the loan was for.

John also provided for his mother, Frances Edwards (A ‘free mulatto woman’) who remained in her home town of Kingston, Jamaica, although by the time John’s will was proven his mother had died.

Shortly after this, Eliza and Peter moved to the newly built, affluent area of Edinburgh, 7 Randolph Crescent, together with Peter’s widowed sister, Janet Commel, née Hill, the widow of James Commel, a merchant, who died in 1836. Their neighbours included the likes of The Honourable Misses Stewart MacKenzie at No. 9 and Erskine Douglas Sandford, advocate and author, who lived at number 11.

The family remained there until Peter’s death in 1837, at which time money was short and Eliza went to live with her married daughter, Lindsay (Hill) Wilson, and her son-in-law, George Wilson, at their home at Dalmarnock, Glasgow, together with her unmarried daughters, Mary Milner, Eliza and Helen, where they were recorded at the 1841 Census.

Eliza died 28 January 1842, and was buried beside her husband Peter Hill in Canongate Kirkyard, Edinburgh. The inventory of her estate for probate in 1848 was just £188 17 shillings, which is about £16k in today’s money.

On a final note to the story, it has been suggested that Peter and Eliza had a son named McCulloch Hill, born in 1796, however, following his life as a shoemaker, I noted no connection between the families, especially as his father’s name according to McCulloch’s marriage certificate, was William.

Sources

Inventories & Accounts of Deceased Estates – Madras 1822-1936. Folio 1227 & 1228

Sir John Lindsay’s will – Records of the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, Series PROB 11; Class: PROB 11; Piece: 1167

Rogers, C. The Book of Robert Burns: Genealogical and Historical Memoirs of the poet, Volume 1.

Constable, T. Archibald Constable and His Literary Correspondents: A Memorial, Volume 1

Elizabeth’s Inventory. 1846 Hill Peter (Wills and testaments Reference SC36/48/32. Glasgow Sheriff Court Inventories).