Following on from our previous articles about career choices in the eighteenth-century, from 1761, we have some more to share with you, so, here goes.

The Barber

The boy, intended for this business, ought to be genteel, active and obliging. To have sweet breath and a light hand. The business of a barber is shaving and making periwigs. The former requires these qualifications and the latter, some ingenuity to imitate all the various fashions introduced by the folly of mankind. But in this trade little learning is necessary. Reading, writing and the common rules of arithmetic being sufficient. There are, however, some periwig makers who do not shave.

The barbers and periwig makers also make a kind of periwig for the ladies; among which they have imported a sort, impudently called the French, as if they intended to affront all the fair who wore them, Téte Moutons, or sheep’s heads. But the English ladies, from their complaisance for that nation, wear the wig, give it the French name and pocket the affront.

Cutting and curling of hair is also another branch of the barber’s business, though others apply themselves wholly to it and are therefore called hair cutters. The wages of a journeyman barber are but small, but if he has a good set of acquaintance and can be settled in a shop advantageously situated, he may set up with fifty pounds.

Bellows maker

This is a very useful and extensive business, bellows being not only made for families, but also for organs, for blowing fresh air into mines and for carrying on a great number of mechanic arts, in many of which they are of very different sizes and constructions, and some of the prodigiously large. It is a profitable business for the master.

Blue maker

They make blue of indigo mixed with cheap materials for the use of the calico printers and dyers, and for bluing of linen when washed, but have nothing to do with the fine colours used in painting. It is a laborious business and is imagined to hurt the nerves. Those who keep shop get a good living. They take an apprentice from ten to twenty pounds, but they give low wages to a journeyman who works from six to eight.

Card maker

The making of playing cards is a very easy business and requires neither judgment, strength nor ingenuity. It consists of pasting several sheets of paper upon each other and then printing off this card paper from wooden blocks. After which the court cards are coloured, the paper glazed and the cards cut out.

The chocolate maker

As the making of chocolate is hard work, mostly performed over a charcoal fire, which is apt to affect some constitutions, the boy who is to be put apprentice to it, ought to be strong and hardy. Chocolate is made of a fruit called cacao produced in the West Indies and other parts of the world. This is a kind of nut about the size of a walnut, which being stripped of its thin shell is worked upon a stone, till it is equally mellow, and then put into tin moulds in which it hardens, and from them receives the form of cakes. To perfume it they mix it with venello (vanilla).

Comb maker

The making of combs is divided between two branches – the ivory and the horn comb makers. The ivory comb makers buy the ivory plates, rasps them to a proper thickness and saws the teeth. They also make combs of box, tortoiseshell and sometimes of horn, in which case they buy the horn ready prepared.

The horn comb maker cuts the ox’s horn into several rings and splits each, when hot, pulls them open and then pressing them between hot iron plates until they are of a proper thickness, shapes them, and afterwards saws the teeth. The horn comb maker does not make combs of ivory etc.

Dial plate enameller

Those of this business make enamelled dial plates, which they sell to the watchmakers. They take the brass plates, cover them with white enamel when wet, make the numerals, and fix the enamel by fire.

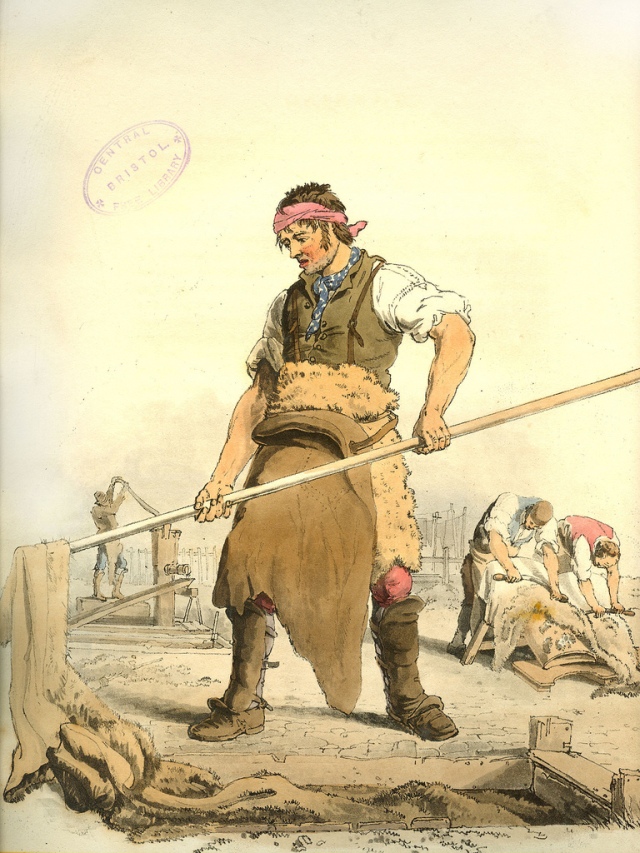

Fellmonger

This is a very nasty, stinking trade, much exposed to wet and cold, therefore not fit for weakly lads. The fellmongers buy up the skins of sheep and lambs, from which they discharge the wool, make the sheepskins into pelts, leather for breeches, alum leather etc. They take from five to twenty pounds with apprentices, who require only a common education. They give very poor wages to their journeymen.

The hatter or hat maker

The hatters, or hat makers, are those who work the wool, hair or fur into a proper substance for a hat. This is called felt. It is very slavish work, the men being continually stopping over the steam of a hot kettle and requires strong lads, who are taken apprentice with ten or fifteen pounds and frequently with nothing. But when out of their time, they may get, as journeymen fifteen or eighteen pounds a week, or set up in this branch with one hundred pounds.

Hour glassmaker

This is a branch which requires very slender abilities to become a master of. He is partly a turner and buys his glass from the glasshouse. There are not many of them, though there are more hourglasses made than is generally imagined, especially for the sea, there not being a ship without several kinds of them, such as hour, half hour, quarter hour and minute glasses. The master will take an apprentice with five pounds who when out of his time may earn ten or twelves pounds a week or with twenty pounds may set up for himself.

The ink maker

Those who are solely employed in making black and red writing ink and ink-powder are but few in number because most retail stationers make ink to supply their own customers. The ink makers take no apprentices since whatever their secrets they may be possessed of it is in their own interest to keep them concealed.

The Loriner or bit maker

The loriner makes bits and all the ironwork belonging to a bridle, together with the stirrups. It is an ingenious and laborious branch of the smith’s business and the beauty of the work consists of filing and polishing.

Pastry Cook

This is a profitable business and requires a boy of activity and industry. The pastry cooks of London have many of their shops elegantly fitted up with carved work, gilding and looking glasses. They daily make all kinds of pastry and sometimes also deal in confections and jellies. They take ten or twenty pounds with an apprentice, who, when out of his time, may have about twenty pounds a year and his board by serving as journeyman, or if he sets up as a master, it will require 300 pounds at least to fit up a genteel shop with built-in ovens etc, but he may set up in a less splendid manner with a hundred pounds.

Snuff Box maker

The use of snuff has naturally produced the introduction of snuff boxes which are made not only of all kinds of metal, either plain, chased or embellished with stones, enamel, shells etc but of ivory, coal or even paper. This has introduced several different trades some of which the makers take ten or twenty pounds with an apprentice, in others not more than five pounds.

I’m sure you know where the expression “Mad as a Hatter” comes from…..

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes, the mercury used in the hat making trade. 🙂

LikeLike