Our present Queen was not the only one to have an ‘Annus horribilis’, for King George III and Queen Charlotte theirs, however, lasted somewhat longer than one year. For them, the years between 1781-1783 could, without a doubt be described as being some of the worst years of their lives with the loss of their two youngest sons. Both parents were devastated by such tragic events.

We begin at the end of March 1781 when the newspapers reported that the queen was once again pregnant with what would be her fifteenth child and that a public announcement would be made at court after the Easter holidays. No announcement came – did the queen miscarry or was it merely ‘fake news’?

Her Majesty is said to be certainly pregnant of her fifteenth child a piece of intelligence that will be publickly communicated at Court after the Easter holidays.

Kentish Gazette, 28 March 1781

Early autumn of 1781 it was reported that young Prince Alfred (born 1780) was dangerously ill and that the queen was constantly attending to her youngest children in the nursery. By October Alfred was deemed to be much better and out of danger. All fourteen children were now doing well, even if the Prince of Wales (later George IV) was giving concern to his parents over his scandalous relationship with Grace Dalrymple Elliott who, at the end of March 1782, produced her one and only daughter reputedly as a result of her liaison with the Prince.

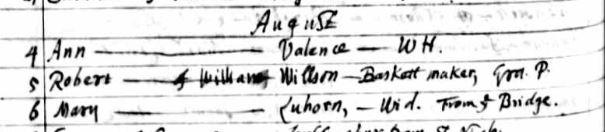

Prince Alfred’s health remained something of a cause for concern and in May 1782, it was agreed that he should be taken to Deal Castle to make use of the salt water there for the benefit of his health. Mid-August his health again deteriorated and on August 20th, 1782, despite Dr Heberden attending to him throughout the night, young Prince Alfred, aged one year and eleven months died of ‘a consumption’; other reports stated that whilst perfectly healthy when he was born, he became weak and died from ‘an atrophy’. A report given in the Reading Mercury amongst several other newspapers stated that:

The queen is much affected at this calamity, probably more so on account of its being the only one she has experienced after a marriage of 20 years, and have been the mother of fourteen children. There will be no general mourning for the death of Prince Alfred, it being an established etiquette never to go into mourning for any of the royal blood of England under fourteen years of age, unless for the heir apparent to the crown.

The young prince’s body will be removed from Windsor to the Prince’s chamber next the House of Lords, where it will be till the time of internment in Henry the VIIth chapel, Westminster Abbey. The queen is now pregnant of her fifteenth children, thirteen of which are living.

The queen – pregnant! We had to find out more.

Her Majesty is now in the seventh month of her pregnancy with her fifteenth child.

Bath Chronicle and Weekly Gazette, 29 August 1782

History tells us that the next child born to Queen Charlotte was Princess Amelia in August 1783, so what of the reported pregnancy in 1782. We thought it must be another piece of ‘fake news’, but seemingly not. The Norfolk Chronicle at the end of April 1782 stated that the queen was ‘in her fifth month of her fifteenth child’.

Another newspaper report regarding the death of Prince Alfred also pointed out that the queen was now ‘big with her fifteenth child’ and another confirmed her to be ‘in the seventh month of her pregnancy’ at that time. So, you would have expected reports in the press about the birth of this child about September or even October – but nothing, not a word, and if a royal child was stillborn, confirmation would still usually appear in the newspapers – very strange!

Although there was no official period of mourning the Royals were not seen out until 7th September when they travelled to Buckingham House from Kew. There are several reports of the queen continuing with her usual duties but still no mention of the pregnancy.

Early May 1783, disaster struck the royal family again when the young Prince Octavius was taken from them.

The queen never left him from Thursday night till Saturday, when he died; his majesty also continued with him from Friday evening till his death. Their majesties are almost inconsolable for the loss of the amiable young prince. Princess Sophia, who was inoculated at the same time it was feared would not recover; but yesterday it was thought the disorder had taken a favourable turn. Prince Octavius is to be interred privately in Westminster Abbey with his late deceased brother Alfred.

After these tragedies, life was to improve for the royal family with the birth of Princess Amelia almost one year after the death of Prince Alfred meaning she was conceived just after the queen would have given birth to the child she had been reported to have been bearing in 1782 – all very strange!