As many of my regular readers will know, I am extremely interested in the life of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire and have written several articles on here about her, but today I am incredibly thrilled to welcome a new guest to All Things Georgian.

Bibi Cox O’Brien graduated from the University of Sheffield in 2022 with a BA and MA in English Literature and is set to go to Oxford University later this year to pursue a DPhil in early modern women’s poetry manuscripts. Her research interests lie primarily in 17th century poetry, but her enduring love is that of women’s literature, and a dedication to honouring women who have made history with their intelligence and literary talents. With that, I’ll hand over to Bibi to tell you all about her discovery.

Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire’s legacy as a figure of immense public interest is both enduring and unsurprising. Her rich life, full of political influence and salacious scandal, has bestowed on her a cultural icon status. Nevertheless, a question remains over what we know about her private self and her innermost thoughts. We know more than enough about the facts of her life, but we know very little about her own opinions of how others saw her, or how she saw herself. However, these questions can begin to be answered with the recent discovery of her 1776 poem ‘To myself’.

Whilst on a work placement at the Chatsworth House Archives, I came across the poem. I was meant to be transcribing letters of correspondence for the work placement but requested some further items from a small archival collection called ‘Papers of Georgiana Cavendish’ which contained what was described as ‘notebooks and scrapbooks.’ I was an MA English Literature student at the time, but I knew I had a keen interest in women’s poetry manuscripts, so when I read a letter by Georgiana’s brother which mentioned some verse written by her that he had circulated amongst peers and had been wildly popular, I wondered if there was something of interest still waiting to be found in the archives. What I ended up finding surpassed my expectations.

‘To myself’ is a deeply personal and private poem, written by Georgiana in 1776, when she was only nineteen years old, yet somehow both predicts and comes to terms with her blossoming fame. At the top is the inscription ‘Althorp’, her childhood home, suggesting this is where it was written, another indicator of her relative youth. In the poem, she articulates a duality of self, expressing the nuances of her identity which existed in private, and how she saw herself in relation to her fame. She clearly and rationally sets out the premise that there are two parts of her, the public and the private sides. She expresses the almost paradoxical qualities which she possesses, whilst maintaining an unyielding self-assurance. It is a remarkable poem, and one which holds the potential for new insights about her character.

Throughout the poem, she uses a direct address to ask herself questions about her own identity, resulting in a rumination on her own sense of self, something which is largely absent from the various biopics and biographies. She sets out two distinctly separate parts of herself, a compartmentalisation which she perhaps used to understand herself and her burgeoning fame. The poem begins with multiple pronouns which express her multiplicity:

‘Tell me myself & if thou canst tell true

What are thy merits & thy failings too

Art thou as some n doubt will think they know

An Idle being merely form’d for show

A trifling toy the plaything of the day

To flutter for a while then fade away

And yield the palm with a reluctant sigh

Whilst newer charms engage each gazer’s Eye’

Her immediate acknowledgement of what others ‘think they know’ about her is striking, and signals that she was aware not only of what she thought of herself, but what others thought of her too. She paints herself as a ‘toy,’ and a ‘plaything,’ a seemingly lifeless object which others use for their own gratification. The revealing phrase ‘reluctant sigh’ suggests again that she was acutely aware of her status as a caricature of aristocratic femininity and prominence as a salacious celebrity figure, several centuries before the arrival of throwaway celebrity culture. However, rather than simply acknowledging her public perception, Georgiana goes on to challenge that perception in comparison with how she saw herself. She asks herself:

‘Say does thy Soul Contract its blunted rays

To live for Admiration & for praise

Say does thy bliss consist in being told

A Flattering tale – Worn out because ‘tis Old’

She answers herself in a forthright tone that she was ‘not formed for vanity alone.’ She continues with a striking sense of self-acceptance of her youthful naivety:

‘Tis true much folly may my faults enlarge

And ‘twould be falsehood to deny the charge

Yet Candour says and what she breathes is truth

Some folly ever was allied to youth’

Her stark revelation that she has vices, and that she can even be prone to vanity, but that she is a complicated woman who is acutely aware of her potential to bring about her own downfall, is an element of her personality which is difficult to ascertain without delving into a primary source such as this. The fact that to a certain extent, some of her weaknesses and flaws did in fact bring tragedy into her life in the end, demonstrates her incredible emotional intelligence in predicting it years prior. It is a bold admission for anyone to make; that they have faults and possess parts of themselves which they themselves are critical of. It is another thing entirely for a young woman on the verge of an extraordinary life to admit it in such beautiful verse.

She continues by using a rich array of imagery, setting up a dichotomy between flowing streams and sturdy trees to express her duality of self. The flowing streams represent vanity and the follies of her youth, which carry her away despite her best efforts to resist. She admits she can be easily carried away by the ‘glittering surface of the stream / I to the substance have preferred the dream.’

At the end of the poem, she uses trees to juxtapose the rapid stream of vanity and to establish a symbol of reason which equally resides within her:

‘Yet oft times too in leisure’s silent grove

Where not a breeze can thro’ the branches move

Where thought seem’d graven on the spreading boughs

To reasons throne my Soul has part’d its Vows’

In these final images, she skilfully paints a pastoral and intimate scene in the solitude of a private moment, where she joins with reason in a metaphorical exchange of vows, providing a contrasting image to that of ‘the plaything of the day.’ Her prevailing attitude it seems, is one of duality. Much like Walt Whitman, who almost 80 years later asserted “I contain multitudes,” Georgiana was compellingly mindful of the two opposing sides of her personality. She is aware she contradicts herself, but her overall message, it seems to me, is that she is capable of being many things at once.

There is the vain side, perhaps the side which popular culture both in her time and to an extent today, have grasped hold of. The fashion icon; the gambler; the adulterer. But what is there all along, and arguably what prevails at the end of the poem, is her reflective, fiercely intelligent side. The part of her which longs for reason and sense, and battles to understand who she really is. It is clear from ‘To myself’ that Georgiana was determined to know herself and to reflect on what it means to have public and private sides. She wrote poetry at only nineteen years old about her own vices and inadequacies, and how others took those weaknesses and turned her into a ‘being merely form’d for show.’ That is, I think, an impressive accomplishment.

Georgiana’s private poetry may hold the key to unlocking her private self. Not the private self which comes with affairs or drug abuse, and which has been drawn out many times before, but her inner monologue. Truly, what it was like to be her. ‘To myself’ has the ability to challenge stereotypes of Georgiana as a vain celebrity, or even as a martyr of tortured women. She was not a passive victim of the patriarchal structures within which she lived, but an active and extraordinarily intelligent woman who possessed a self-awareness rare in any teenager. If this is how she felt at nineteen, it may be safe to assume that in later years, she only became more self-aware. She had weaknesses, as does everyone, but her weaknesses should be embraced, and she should be viewed as a complicated and nuanced woman, just as she saw herself.

You can read a full transcription of ‘To myself’ on the Chatsworth House website: https://www.chatsworth.org/visit-chatsworth/chatsworth-estate/art-archives/devonshire-collections/archives/to-myself/

You can listen to Bibi on BBC Woman’s Hour, in discussion with historian, Dr Amanda Foreman, author of Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire.

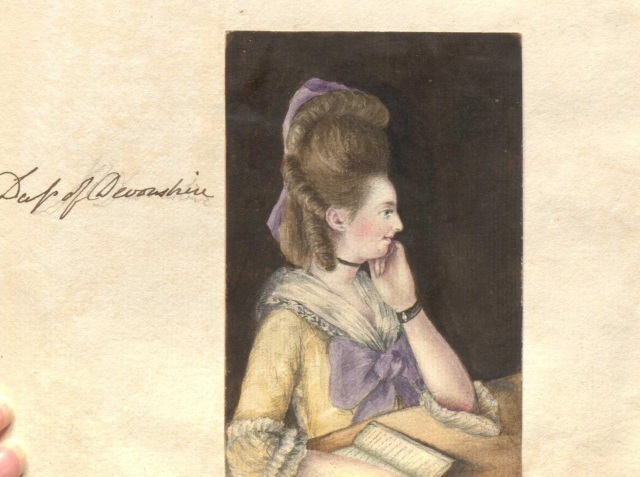

Featured Image

Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire after 1778. Courtesy of Royal Collections Trust