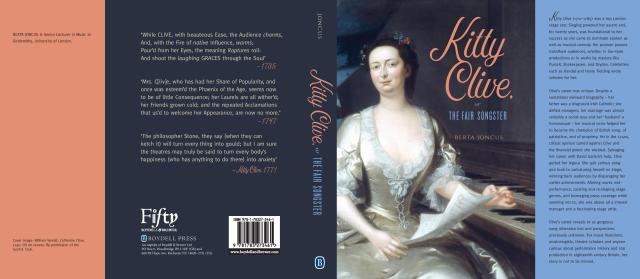

Today I have the honour to host a guest post about the famous 18th-century celebrity, Kitty Clive, by Dr Berta Joncus.

Berta is Senior Lecturer in Music at Goldsmiths, University of London. Before joining Goldsmiths, she was at the University of Oxford: she took her doctorate there and was a British Academy Post-Doctoral Fellow at St Catherine’s (2004–7), then music lecturer at St Anne’s and St. Hilda’s (2007–9). As a scholar, she focuses on the intersection in eighteenth-century vocal music of creative practice and identity politics.

Historians have typically described Kitty Clive as a fat, vain comedienne. My book reveals another artist altogether.

From her 1728 debut until 1748, Clive was an awe-inspiring songster who changed Georgian playhouse history. She was the first playhouse performer to make music the basis of her stardom. She upended hierarchies of taste, dazzling equally with smart airs, operatic pyrotechnics and raw street ballads.

Was she a cheeky minx, a refined siren, a leering vulgarian, or all or none of these? Audiences flocked to the playhouse to find out. Handel, Thomas Arne, Henry Fielding, David Garrick and others supplied vehicles for personae Clive re-invented on the boards, defying male authority through her ability to, as she once wrote, “turn it & wind it & play it in a different manner to his intention.”

Facing systemic discrimination against women, Clive strategized brilliantly. She had some lucky breaks: in 1728, as she prepared for her debut, the collapse of London’s Italian opera company deprived audiences of high-style song, and The Beggar’s Opera whetted appetites for low-style song.

Composer and singing master Henry Carey had groomed Clive to excel in operatic and ballad singing, and Drury Lane manager Colley Cibber, desperate to rival other houses, hired the seventeen-year-old on first hearing. Carey was Clive’s friend and ally, fitting her earliest parts to her strengths, whether as a singing goddess (in masques), a witty shepherdess (in ballad opera), or a sentimental heroine (in sung comedy). Like Carey, the playwrights Charles Coffey, James Miller, and William Chetwood – this last Drury Lane’s prompter, and Clive’s first biographer – designed flattering stage characters around her gifts.

But often Drury Lane managers’ casting disadvantaged Clive, forcing her to create her own opportunities. Performing in The Devil to Pay, a 1731 ballad opera that extolled wife-beating, she used the songs Coffey had added to transform Nell, scripted as the drab victim of her cobbler husband, into a tender, courageous heroine. Overnight, she became Drury Lane’s star of ballad opera as well as of serious song.

In 1732 Cibber replaced Carey with Fielding as Drury Lane’s author of Clive vehicles, driving the indebted Carey to suicide and saddling Clive with Fielding’s unsavoury characterizations – in comedies, epilogues and air verses – through which she nonetheless shone.

With success came marketing. Illustrator John Smith claimed that an image he had engraved of a bare-breasted nymph from an old Dutch oil was a likeness of Clive igniting a years-long battle over whether she was plain or comely.

![After Gottfried Schalcken [Couple d’amoureux dans un forêt, c1695], MISS RAFTER in the Character of PHILLIDA, 1729. Mezzotint. © Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Museum number: S.3874-2009.](https://georgianera.files.wordpress.com/2020/04/fig.-2-miss-rafter.jpg?w=519&h=729)

![Fig. 6.6. Alexander van Aken after Joseph van Aken, ‘Of all the Arts…’ [Catherine Clive, ‘Printed for T. Bowles’], 1735. Mezzotint. © Trustees of the British Museum. Museum number 1902,1011.6026.](https://georgianera.files.wordpress.com/2020/04/fig.-4-of-all-the-arts-clive-van-aken-after-van-aken-1735.jpg?w=640)

While pamphleteers attacked her, she shored up her reputation by appearing to marry into the genteel Clive family of Shropshire. This ‘union’ was perhaps the most brilliant invention of the former Kitty Raftor: it bestowed on her the status of a Clive while allowing her to keep her earnings, and hid the same-sex desires that both she and George Clive harboured. Kitty’s reputation for propriety – one satire glossed her as ‘Miss Prudely Crotchet’ – became a critical means for garnering sympathy once Theophilus Cibber returned victorious as Drury Lane’s deputy manager.

In 1736 the younger Cibber tried to steal Clive’s parts for his new wife, Susannah. Rewriting the rules of playhouse power, Clive ran a newspaper campaign about her rectitude and her right to her parts; this battle Theophilus lost, despite having the more credible behind-the-scenes account.

Dissimulation was one of Clive’s arts, and her ability to shape-shift made her a Town favourite. She appealed to wit, not sensuality, and claimed to speak for the middling sorts. In her airs and parts of the 1730s and 1740s, Clive protested against effeminate fops, foreign entertainers, men’s authority, Spain’s perfidy, and first minister Robert Walpole’s corruption.

‘The Clive’ stood for native taste in music (she was given two parts in London’s favourite masque, Comus), in legitimate drama (her Portia in The Merchant of Venice became legendary), and in celebrity connections (Handel wrote Samson for her to lead, and an elegant air for her 1740 benefit). In propria persona ‘Kitty’ roles multiplied, not least from the pen of Garrick, so that she could effervesce in the playhouse, season after season.

Clive’s very success sowed the seeds her failure. When in 1743 Drury Lane manager Charles Fleetwood cheated company members of their salaries, she co-led a company rebellion, prompting Fleetwood to claim that the house had been bled dry by stars’ outrageous salary demands.

He published Clive’s earnings, which were indeed large, and the perennial eagerness of the celebrity industry to consume its own children did the rest. Critics charged her with being vain, greedy, jealous and ambitious; a story was faked that she had been involved in a back-stage scuffle with rival actress Peg Woffington. In December 1745 Susannah Cibber engineered another press row with Clive, but this time readers believed her, not Clive. By 1747, Clive had lost her following.

Needing to work to support herself, her brother, and their household, Clive colluded with new Drury Lane manager Garrick to regain public favour. He re-cast her as a blousy, arrogant has-been whose saving grace was how cruelly she mocked herself. To verify Garrick’s version of her, Clive wrote and led self-incriminating in propria persona afterpieces; in her first such work, The Rehearsal, or Bays in Petticoats (1750), she also staged her farewell to serious song. Clive would again succeed at Drury Lane, where she would dominate for another twenty years, but in farce rather than art song or drama. She retired early and wealthy, but her former reputation as a vocal artist of rare skill, and an exponent of British virtues, was in tatters.

Kitty Clive’s rich, complex story, both familiar and foreign to our own celebrity-obsessed era, has been buried under mis-information for centuries. In Kitty Clive, or The Fair Songster, I invite readers to appreciate for the first time not only her achievements as a singer, actor, writer and self-manager, but also the obstacles she had to overcome and the compromises she had to make to reach, and regain, her leading position on the London stage.

***

For a signed author’s copy at £35.00 (or $45.00) posted free of charge, please email b.joncus@gold.ac.uk.

To listen to the song Handel composed in 1740 for Clive, please to go this link.

Thank you for a post about an interesting singer of the 18th century. Are there posts about others, such as Peg Waddington whom you mention.

Her life seems worth of a movie or biopic.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Such an interesting and turbulent life this woman led! Loved reading about 18th century celebrity culture and how fame was as fickle then as it is now. Thanks for this post!

LikeLiked by 1 person

“Was she a cheeky minx, a refined siren, a leering vulgarian, or all or none of these? Audiences flocked to the playhouse to find out…”

LOL – I particularly enjoyed that part. Here’s to women – or anyone, I suppose – who makes the most of the options available to them in addition to creating a few where none were thought to exist!

LikeLiked by 1 person