I am delighted to welcome, a now regular guest to All Things Georgian, Elaine Thornton and today she is going to tell us all about the dining etiquette at the Georgian table, the pleasant and not so pleasant aspects of it and with that thought I will hand you over to Elaine to explain!

For the lucky few at the top end of Georgian society, dining and entertaining lavishly was an everyday affair. Dinner was the main meal of the day, although the timing changed as the century progressed, moving from mid-afternoon to early evening. Few people ate a formal lunch. Most either missed the meal out altogether or had a small snack in the middle of the day, often consisting of cold meat and fruit.

There was a good deal of ceremony surrounding a Georgian dinner party. Seating was ordered by status: women took precedence over men of the same rank, while married women ranked above unmarried ones. Conduct books warned that ‘nothing is considered as a greater mark of ill-breeding, than for a person to interrupt this order, or seat himself higher than he ought’. Indeed, the seating etiquette was so rigid that the son of a French duke visiting England in 1784 remarked that ‘for the first few days I was tempted to think it was done for a joke’.

Once the guests had seated themselves in the correct places, the dishes were brought in by servants and placed down the centre of the table. Diners then carved and helped themselves from the dishes nearest to them. Servants were expected to efface themselves in the presence of their betters, ‘to tread lightly across the room, and never to speak, but [only] in reply to a question asked, and then in a modest under voice’. A badly behaved or ignorant servant was ‘a reflection on the good conduct of the mistress or master’.

Dinner would consist of at least two courses, heavily dominated by meat and fish dishes. A cookery book of the time gives the following as an example of a routine menu: First course: mock turtle soup, white soup, rump of beef, lamb pie, pigeons, ducklings, veal, boiled chickens, spinach; Second course: green goose, fried soles, boiled trout, stewed oysters, chickens [again], leverets, larks, macaroni and almond cakes.

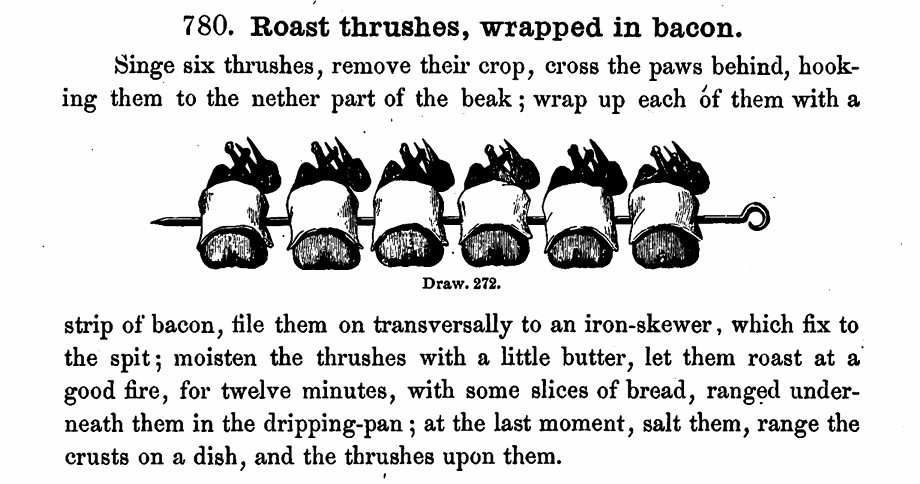

Songbirds such as larks and thrushes were considered delicacies. A recipe of the time for ‘small birds in a savoury jelly’ emphasises that the birds should be put into the jelly with their ‘heads and feet intact’. Turtles were also considered a luxury item, and special turtle dinners were popular. Beef was, and still is, a traditional favourite, but the Georgian table included some animal parts we no longer eat, such as lambs’ ears and coxcombs. In 1763, after dining with the chaplain of New College, Oxford, Parson Woodforde remarked in his diary that ‘I shall not dine on a roasted tongue and udder again very soon’.

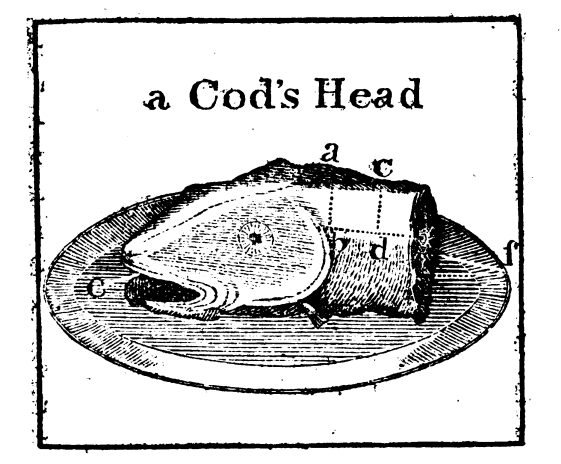

Carving could be a minefield for the inexperienced: ‘We are always in pain for a man, who, instead of cutting up a fowl genteely, is hacking for half an hour across a bone, greasing himself, and bespattering the company with the sauce.’ Some dishes were more difficult than others to deal with: ‘There are many delicate bits about a calf’s head, and when young, perfectly white, fat, and well-dressed, half a head is a genteel dish … In serving your guest with a slice of head, you should enquire whether he would have any of the tongue or brains, which are generally served up in a separate dish.’ Cod’s head was likewise considered ‘a very genteel and handsome dish if nicely boiled … Some like the palate and some the tongue [but] the green jelly of the eye is never given to anyone.’

Gentlemen were advised to serve the ladies with their food, but not to be too generous with the portions: ‘As eating a great deal is deemed indelicate in a lady (for her character should be rather divine than sensual), it will be ill manners to help her to a large slice of meat at once, or fill her plate too full.’ Ladies were advised to eat something at lunchtime, to take the edge off the appetite. Otherwise, as eight or more hours could elapse between breakfast and dinner, the ‘half-famished beauty’ might be tempted to make a hearty meal. This could be disastrous for both health and looks: ‘How must the constitution suffer under the digestion of this melange! How does the heated complexion bear witness to the combustion within!’

Some of the advice on how to behave at table is only common sense and courtesy to others: ‘it is exceedingly rude to scratch any part of your body, to spit, or blow your nose, if you can possibly avoid it’. Other warnings throw an interesting sidelight on Georgian habits: ‘Pick bones clean and leave them on your plate; they must not be thrown down, nor given to dogs in the room’, and ‘In eating fruit, do not swallow the stones, but lay them and the stalks on one side of your plate’. Confusingly, advice could vary from book to book: one writer recommends that ‘You should bend towards your plate when you are eating, that prevents your dirtying the cloth’, but another maintains that ‘eating your soup with your nose in the plate is vulgar’.

Polite conversation at table was an important part of the ritual. Dr Johnson recommended that serious subjects should not be discussed at table, as ‘people differ in opinion, and get into bad humour, or some of the company who are not capable of such conversation are left out, and feel uneasy’. He added, ‘It was for this reason, Sir Robert Walpole said, [that] he always talked bawdy at his table, because in that all could join’.

Wine was usually drunk at dinner. The Georgians’ consumption of alcohol was sky-high by our standards: in its December 1770 issue the Gentleman’s Magazine listed over eighty ways of saying that a person was drunk, ranging from the familiar ‘intoxicated’ to ‘cup-stricken’, ‘bosky’, ‘Tipperary’, ‘on a merry pin’ and ‘cherry-merry’. However, while drunkenness in men was accepted, women were not supposed to become inebriated in polite society. Indeed, it was considered improper for a woman even to request a glass of wine at dinner: ‘As it is unseemly in ladies to call for wine, the gentlemen present should ask them in turn, whether it is agreeable to drink a glass of wine’.

For the men, imbibing large quantities of wine at table had inevitable consequences, but while the ladies were still present, a certain level of decorum had to be maintained: ‘If you are obliged to leave the dining room at any time to relieve yourself, you should endeavour to steal away unperceived, or make some excuse for retiring … on your return, be careful not to announce that return, or suffer any adjusting of your dress’.

An American traveller in Regency England, Louis Simond, expressed his surprise and distaste at a custom he noted which took place at the end of the meal, when a glass bowl of water was placed before each diner, who proceeded to ‘stoop over it, sucking up some of the water and returning it, often more than once, and with a spitting and washing sort of noise, quite charming – the operation frequently assisted by a finger thrust elegantly into the mouth!’.

A Frenchman visiting Britain in the 1780s witnessed the same behaviour, which he described as ‘a custom which strikes me as extremely unfortunate’. He added that the more fashionable people washed their hands in the water instead of rinsing their mouths out with it, which he found equally unpleasant, as the water became ‘dirty and quite disgusting’ – which does not say much for the cleanliness of the diners’ hands.

At the end of the meal, the ladies retired, leaving the men to continue drinking for a while. Once they had left the room, standards of behaviour could slip drastically. Louis Simond noted in amazement that ‘in the corner of the very dining room, there is a certain convenient piece of furniture [a chamber pot] to be used by anybody who wants it. The operation is performed very deliberately and undisguisedly, as a matter of course, and occasions no interruption of the conversation’.

Decorum was restored, however, when the gentlemen re-joined the ladies, to spend the remainder of the evening in a more relaxed fashion, playing cards, listening to music, chatting and drinking tea. For those who still felt able to fit in a little more food, a light supper might be offered before retiring.

Sources

Anon, The Man of Manners, or Plebeian Polish’d, 1737

Anon, The Mirror of the Graces or The English Lady’s Costume, 1811

Anon, The Polite Academy, 1768

James Boswell, Life of Johnson, 2008

Gentleman’s Magazine, 1770

Francis Collingwood and John Woollams, The Universal Cook, and City and Country Housekeeper, 1792

Louis Simond (ed. Hibbert), An American in Regency England, 1968

Matthew Towle, The Young Gentleman and Lady’s Private Tutor, 1770

John Trusler, The Honours of the Table, London, 1791

John Trusler, Principles of Politeness, 1775

T.H. White, The Age of Scandal, 1986

James Woodforde (ed. Beresford), The Diary of a Country Parson, 1999