As there is so much to tell in this story, during the next articles I will be taking a look at the life of Catherine Despard and that of her son, so do keep an eye out for the following parts.

Firstly though, I would like to give a massive ‘Thank you’ to the kindness and generosity of Mike Jay, author of The Unfortunate Colonel Despard, who kindly shared with me Sarah Gordon’s will, which helped to open some doors. To Mish Holman, who, despite being busy with her own research, found time to check out some documents at the National Archives for me and to Professor Gretchen Gerzina for telling me to ‘go for it’ when I initially thought everything known about Catherine had already been written.

For fans of the programme, Poldark, you may well have seen the episode about Edward (Ned) Marcus Despard and his wife, Catherine and her valiant, but unsuccessful, attempt to save her husband’s life.

Whilst Poldark is fiction, the lives of Edward (Ned) and Catherine were real. The programme, as you might expect, used quite a bit of creative licence in the telling of their story, especially as neither character appeared in the books by Winston Graham.

Much has been written about the life and more dramatically, the death of Edward, who, for those who don’t know, was found guilty of high treason and met his end courtesy of the hangman’s noose, closely followed by the removal of his head, which was placed on a spike as a warning to others.

Edward allegedly plotted along with his co-conspirators, to kill George III whilst on his way to Parliament on 23 November 1802, then to seize the Tower, and the Bank of England. Whether he was guilty or not is another story, as he refused to admit to anything, perhaps to avoid implicating his co-accused. I’ll leave you to read more about the trial for yourselves, as the focus in tis post is really upon his wife, Catherine.

Fewer than a handful of writers have attempted to record in any detail Catherine’s life, and so, always being one for a challenge, it was suggested that I try to see if I could piece together a little more about the life of the woman who stood beside Edward every step of the way, until he mounted those final steps on 21 February 1803.

Not only did Catherine seem to be a dutiful and loving wife, but she also acted as a courier and campaigner, visiting her husband, writing letters on his behalf and fighting as hard as she could to gain his freedom.

Who was Mrs Catherine Despard?

Accounts vary but, she is often described ‘a former black slave‘, from somewhere in the Caribbean, but we do know a little more about her than just those few words.

Catherine’s early life

To begin with though, we don’t know exactly when, or for sure where Catherine was born, but it now seems fairly safe to assume she was born around 1760, give or take a few years, in Jamaica.

Having trawled through the baptism parish registers for Jamaica, there are a few possible matches for Catherine, as below, from the parish register of St Catherine’s Jamaica, but there is nothing conclusive. This entry provides no parents being named but describes her ‘a mulatto child’ meaning one white parent, one black which could possibly be hers.

It is now known that Catherine’s mother was Sarah Gordon of St Andrew’s, Jamaica, who was buried on 25 July 1799 at Long Mountain, St Andrews, as can be seen here.

It is now known that Catherine’s mother was Sarah Gordon of St Andrew’s, Jamaica, who was buried on 25 July 1799 at Long Mountain, St Andrews, as can be seen here.

The parish register of St Andrew’s clearly states any person of colour or black and as you can see the entry directly above Sarah Gordon’s, states that Martha was ‘a free black woman’, the next but one entries after Sarah’s name, tells us of two women who were buried as ‘a woman of colour’ and yet there is nothing against Sarah’s name, which is unusual in light of the other burials recorded at St Andrews, but this could simply have been an omission. The burial entry also tells us she was not buried in the church graveyard, but at Long Mountain.

Sarah left a will, of which I was extremely kindly sent a copy, by Mike Jay (see bibliography at end of the whole article). The handwriting not the easiest to decipher and is quite faint, but it does tell us that Sarah was a ‘free black woman’.

I have read that Catherine’s father was a church minister, but I haven’t as yet been able to confirm the source. Mike Jay also said that ‘There was a claim in the London pamphlets of 1802 that her father was a Jamaican preacher and her mother a Spanish creole’ but he had no luck confirming this either.

When writing her will, Sarah was ‘sickly state of health, but sound of mind.’ She was a land owner of the parish of St Andrews, and sadly no mention of a husband, it simply describes her as being a relic i.e., widow.

Although very difficult to read, the will tells us that at some stage in the past Sarah had borrowed money from a friend or possibly a relative, Hannah Williams, a ‘free sambo woman’. Sarah part purchased three pieces of land in Kingston, half of the money for the three plots was funded by her, the remainder of the money borrowed from Hannah, which Sarah wished to be paid to Hannah upon her death. She also names Hannah’s two children, Eleanor and Benjamin Pierce, who, in the event of Hannah’s death, would take over ownership of the land, assuming they were aged 21 or over.

Both children named in the will were born in St Andrews, Jamaica, Eleanor in 1783 followed by Benjamin, 1791, but what is confusing is that both children shared the same father, a Benjamin Pierce, but the mother of Eleanor was named as Johanna Williams, whilst Benjamin’s mother was a Hannah Pierce. It’s interesting to note in the parish register, just below Sarah’s burial was that of a Joanna Williams, was this Eleanor’s mother? once again, we may never know.

The children were baptised on the same day in January 1799, a fact that Sarah would, in all likelihood have been aware of. Whilst that is a slight aside, Sarah also names her sister, Catherine Pierce (surname illegible), so quite who her middle name, Pierce was in honour of, I don’t know, but what does seems highly probable is that Sarah named her daughter, Catherine, in honour of her sister.

Sarah also left a legacy for her daughter, Catherine:

to my dear daughter, Catherine Gordon Despard, now in London … four negroes, who had been in my possession, a negro man named Jack and a negro woman, named Maria and a little boy, her child, named December and a negro woman, named Louisa.

It has not been possible to find out anything more about the enslaved people or what became of them, unless Catherine bought them over to England, which seems rather unlikely. Sarah also described Catherine as

my beloved daughter and best of friends, Catherine Gordon Despard of the city of London‘

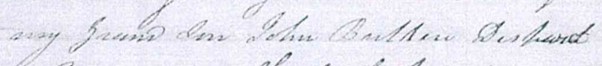

It would seem clear from Sarah’s will, that Catherine was very much loved, but perhaps more importantly that her mother knew about her husband, Edward, where they were living and also that Catherine and Edward had a son, Sarah’s grandson, John (illegible) Despard.

Sarah knew that her grandson was a lieutenant in His Majesty’s East London Regiment, so despite Catherine having left Jamaica almost 10 years previously she was aware of her grandson’s military rank prior to her death, which must mean that they retained communications after Catherine left the island, so presumably Catherine wrote to her mother with news from England.

This link will take you to Part 2 and Catherine’s arrival in England and this one to part 3.