This portrait caught my eye recently whilst looking at portraits by Gainsborough and I was curious to know a little more about her, especially as she was sporting the high hair fashion of the day.

She was Carolina (not Caroline as noted in many places) Alicia Fleming, born in 1755 to parents Gilbert Fane Fleming and Camilla Bennet. It’s worth mentioning that Carolina’s maternal grandparents were Charles, Bennet, 2nd Earl of Tankerville (1697-1753) and Camilla Colville (1698 -1775). Camilla being a Lady of the Bedchamber to Queen Caroline and afterwards to the Princess Augusta.

In July 1776 Carolina married the baronet, John Brisco (1739-1805). It was just one year after their marriage that Carolina’s father died, and in his will he made provision for Carolina’s husband to take over ownership of his two plantations on the island of St Christopher, Westhope in St Peters Basseterre and Salt Ponds in St Geo. Basseterre.

Of course, along with the plantations were slaves, in this case the couple inherited a considerable number to work on the plantations. So far as I can tell the couple spent no time at their plantations, presumably preferring to leave them to be managed on their behalf and simply reaping the rewards from the crops. The couple owned several properties around the country including their country estate, Crofton Hall in Cumbria and a house on Wimpole Street in London.

The couple had seven known children, although most sources imply that there were just three. The seven being, Camilla born 1777, their son and heir Wastel in 1778, Caroline the following year, Fleming John in 1781, Augusta in 1783, Emma the next year, followed by Frederick in 1790 and finally, Henry in 1796.

In 1804 just prior to his death, Sir John Briscoe also purchased Alexander Pope’s house at Twickenham, which Lady Briscoe retained for just a couple of years after his death before selling it in 1807 to Baroness Howe of Langar, who, having already demolished Langar Hall, went on to demolish Pope’s house too.

After the death of Sir John, his son and heir, Wastel, inherited all the estates and in November 1806 he married Sarah Lester, daughter of a Mr Ladbrook. Now, despite producing three children including a son and heir, this marriage that proved to be something of a disaster. It is from this point onwards that Lady Carolina’s story has, I’m afraid, been hijacked by that of her son, Wastel. Please be aware, it does not make for pleasant reading from this point onwards.

By 1813, Lady Sarah had had more than enough of her husband and took him to court for cruelty and adultery. This was to prove to be an incredibly lengthy affair lasting for over ten years. Lady Sarah remained at their home in London, whilst her erstwhile husband went to live in their country estate in Cumbria.

As well as the issue of adultery the tricky subject of money reared its ugly head and how much money each of them had and how much they believed they should have as a result of a possible divorce.

Lady Sarah made quite a few purchases for items she needed, not least clothes, as it would appear that during their dispute, Sir Wastel burnt most of her clothes which were valued at in excess of £200 (which is about £10,000 in today’s money).

Sir Wastel however, disputed, not the burning, but the value of the said clothing, and according to him they were worth a mere £10 or £500 in today’s money. Lady Sarah stressed that she not only required new clothes, but that she needed sufficient money from him to live in the lifestyle she was accustomed to and to ensure that his children were well provided for.

Eventually the court allocated Lady Sarah £200 a year, plus £200 a year pin money, but the battles over money continued for years, with Lady Sarah claiming that her husband had been having a relationship with a servant at their home in London, one Sarah Stow of Norfolk. He in turn, accused her of adultery.

Sir Wastel moving out of the marital home and set up home with his mistress, eventually moving to their country residence in Cumbria, where Sarah Stow continued to live as his ‘housekeeper’. Sarah Stow by this time also used the surname Stageman.

The couple, once free of Lady Sarah, although not legally, went on to have at least eleven children, all baptised with just Sarah Stow’s name, no father was named, but you would have thought everyone in the local area would have easily put two and two together to work out who the father was.

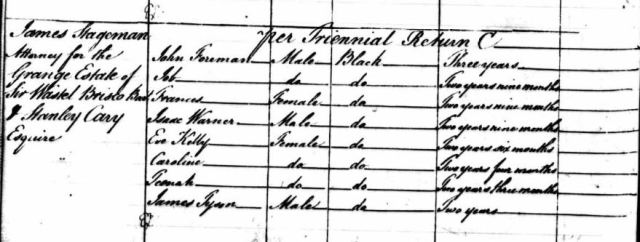

It isn’t until you look at her will, which was proven 1853, that you notice that she referred to herself as Sarah Stageman, otherwise Stow. There’s no explanation as to why she used the name Stageman, but it’s you take a look at the slavery register for 1827-1828 for slaves owned by Sir Wastel, that a familiar name appears, in the form of his attorney – a James Stageman. It’s such an unusual surname that he must surely, in some way be connected to Sarah, but to date I’ve no idea how.

Sir Wastel died 1 October 1862 at his country home, at which time his son and heir inherited the title and estate, but what became of his wife, Lady Sarah?

After several years spent intermittently living apart, Sir Wastel stopped paying alimony and found himself back in court, well he would have, had he bothered to appear, instead found himself in contempt of court.

It was in June 1826, that Lady Sarah found herself accused of adultery with the Sir John Winnington, by his wife. In this instance Lady Winnington was granted her divorce as the evidence was clear, he was guilty of adultery with Lady Sarah.

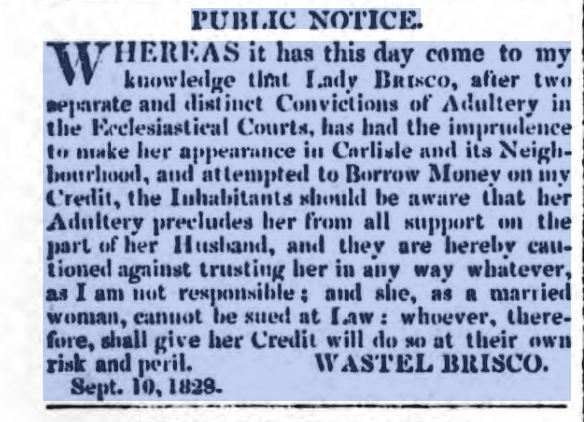

Lady Sarah’s battle with her husband, as they were still not divorced, continued to rage, so much so that he took out the following advertisement in the local newspaper.

Yet again, in 1830, Sir Wastel found himself in court this time, it was a case against him for non-payment of accounts due to a Mr David, that had been accrued by Lady Sarah. On this occasion a number of witnesses were called who testified about the nature of Lady Sarah’s relationship with her husband.

One witness said she had seen him in a compromising position with another woman, another witness, that she had seen Lady Sarah coming downstairs with blood pouring from her mouth and how cruelly she was treated by her husband. Another that she often had cuts and bruises on her body, had her hair pulled out in handfuls, and had been locked in her room with no food or water, the list went on and made for shocking reading. In a nutshell he said that he would persecute her for as long as she lived, which seemingly he did. The judge found in favour of Sir Wastel and that he was not liable for Lady Sarah’s debts.

Life just even worse for Lady Sarah when in 1833 she found herself spending two months in the house of correction at Coldbath Fields, for libel. A few years later she found herself in court once more, again for libel. Lady Sarah died in 1840 and had spent the majority of her life living in fear of her husband and being pursued by him to the end.

Sources

Legacy of British Slave-Ownership

The Annual Register 1817

Office of Registry of Colonial Slaves and Slave Compensation Commission: Records; Class: T 71; Piece Number: 258

Records of the Prerogative Court of Canterbury, Series PROB 11; Class: PROB 11; Piece: 2173

Saint James’s Chronicle 23 April 1825

British Press 24 June 1826

Evening Mail 13 December 1830

Featured Image

Carlisle Cathedral and Deanery above Old Caldew Bridge. Matthew Ellis Nutter (1795–1862) (attributed to). Tullie House Museum and Art Gallery

Fascinating as always

LikeLike

Thank you so much, Basia 🙂

LikeLike

Poor Lady Sarah, what an unhappy life she had.

LikeLike

I know, I really wasn’t expecting what I unearthed when I started this piece 😦

LikeLike

Interesting but such a sad story. It’s sad the court was in favor of the abusive husband.

LikeLike

Unfortunately that’s the way things went at that time, the woman rarely won course cases 😦

LikeLiked by 1 person

What a terrible story behind such a beautiful portrait! Thank you for investigating and sharing with us!

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re most welcome. Sorry it’s so sad though 😦

LikeLike

Pingback: Merkwaardig (week 10) | www.weyerman.nl

Sarah stow was born Sarah stageman. I am descended from her brother Robert. The family came from marsham in norfolk. Another descendent has a letter in which Sarah has died but at the end expressed regret for her life. Presumably her long affair with wastel brisco. There is a grave in thursby where Sarah rests along with many of her children by wastel

LikeLike

Thank you so much for sharing this. I’ve just found her baptism, so her father was Christopher, I wonder who the James was, perhaps her brother or uncle? How brilliant that someone has a letter about her, but how sad that she regretted her life.

LikeLike

I would imagine that she suffered through having illegitimate children at a time when it was considered scandalous. We will never know the context of why she accepted in effect a lifetime of being a mistress. At one court case when she was accused of wrongfully dismissing servants, the judge pointedly made a comparison to the servant fired of good character and Sarah,s affair with brisco ie that she was not of good character

LikeLiked by 1 person

No Sarah’s parents were John stageman and susannah ulph. She was one of 10 living children. James was one of her brothers

LikeLike

Yes, you’re quite correct, I hadn’t spotted her in my quick search. James being her brother makes sense then 🙂

LikeLike