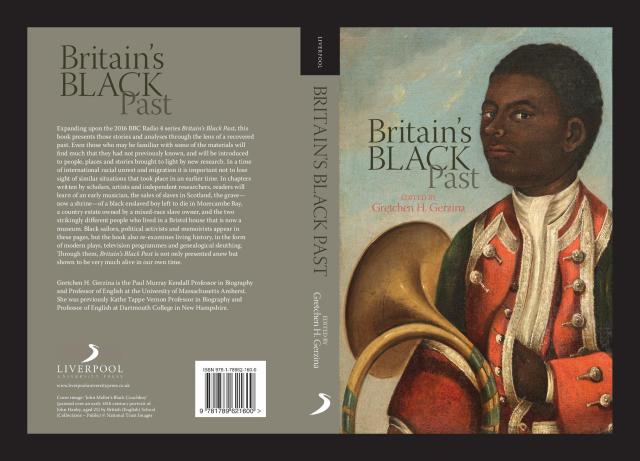

Today, I am delighted to welcome to All Things Georgian, Professor Gretchen Holbrook Gerzina whose new book, ‘Britain’s Black Past‘ (*see end) has just been published by Liverpool University Press and is also available from Amazon. Our paths crossed as a result of our shared interest in the life of Dido Elizabeth Belle, who features in the book.

Gretchen has been an Honorary Fellow at Exeter University, Eastman Professor at Oxford University, and professor of English at Brunel University. She is Paul Murray Kendall Professor of Biography and Professor of English at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and amongst her numerous books, she has written ‘Black England: Life Before Emancipation’. With that introduction, I’ll now hand over to Gretchen to tell you more about how her latest book came to be written.

In 2015, I was contacted by a radio producer, Elizabeth Burke, proposing a ten-part series on early black Britain for the BBC. She had read my book Black England: Life Before Emancipation and thought that would like to put together a number of programmes we called “Britain’s Black Past,” exploring what to most Britons was the unfamiliar history. (You can also listen to the broadcast on BBC Radio 4 by clicking on this link).

My job, as an author with an extensive history of radio presenting, was to go with her to locations all over Britain to interview those who were making discoveries and bring their work to life in the studio. Together we climbed a hill in Wales, visited an enslaved boy’s grave in Morecombe Bay at low tide with Alan Rice, learned from academics led by Simon Newman in Glasgow who had put together a database of runaway enslaved people in Scotland.

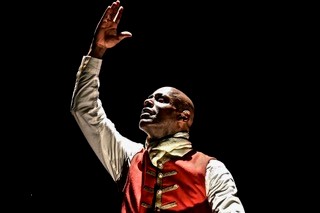

In the studio, Elizabeth and I, with her colleagues, put it all together with further interviews, period music composed by the eighteenth-century shopkeeper and letter-writer Ignatius Sancho, whose letters were read aloud by the actor, Paterson Joseph.

The programmes were such a success when it aired in 2016, that it occurred to me that the finds of those who appeared on-air, and of those we were unable to include at the time, would make a terrific book.

Some of its contributors are academics, but others include independent researchers, a museum curator, an actor, a media specialist, and a lawyer turned biographer. In this book, you will meet an early black trumpeter who is the subject of blogs by Michael Ohajuru, and visit a Georgian house in Bristol where two very different enslaved people lived, explored in chapters by Madge Dresser and Christine Eickelmann.

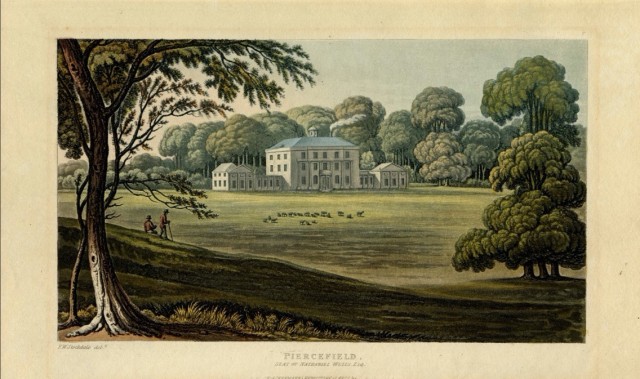

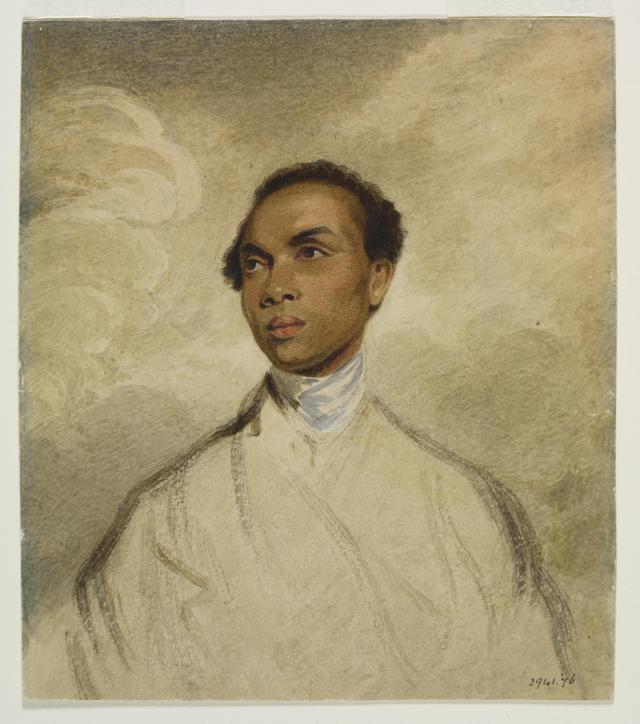

Readers—even those familiar with some of the figures and history it explores—will find much to surprise them. Nathaniel Wells, the mixed-race son of a plantation owner and an enslaved woman on St Kitts, became his father’s heir. He was sent to England for education, and when he came into his contested inheritance built a grand house on his estate and pleasure gardens in Wales. He married twice to white Englishwomen, had numerous children, and became a magistrate and sheriff. His story is complicated by the fact that his money came from a slave plantation, and the only enslaved people he freed were related to him. His story results from the tireless research of Anne Rainsbury, Curator of the Chepstow Museum.

Francis Barber (the servant of Samuel Johnson), black sailors, and Soubise (the ne’er-do-well protégé of Ignatius Sancho) appear in chapters by Michael Bundock, Charles Foy, and Ashley Cohen. Sue Thomas gives a far more extensive context to the narrative of Mary Prince, whose narrative hugely influenced the British abolitionist movement.

Theresa Saxon follows the actor Ira Aldridge through his lesser-known performances in provincial theatres as well as in London, and the ways they were reported in the press.

Rafael Hoermann analyses the political speeches of the firebrand reformer Robert Wedderburn. Caroline Bressey moves forward into the Victorian period to examine how race made its way into literature and public discourse. And Kathleen Chater, whose important database of black people from Britain’s past has become a valuable resource for researchers, discusses the different ways that academics and genealogists contribute to our knowledge of the black past.

These stories may have taken place in the past, but they also live on in the present. Paterson Joseph was so taken by Sancho’s story of becoming independent and later being the first black man in England to cast a vote, that he wrote and performs in a one-man play that travelled from Britain to America.

My chapter reconsiders an ‘All Things Georgian’ favourite, Dido Elizabeth Belle, filling out more of her story but also looking at the ways it has been retold in television and film.

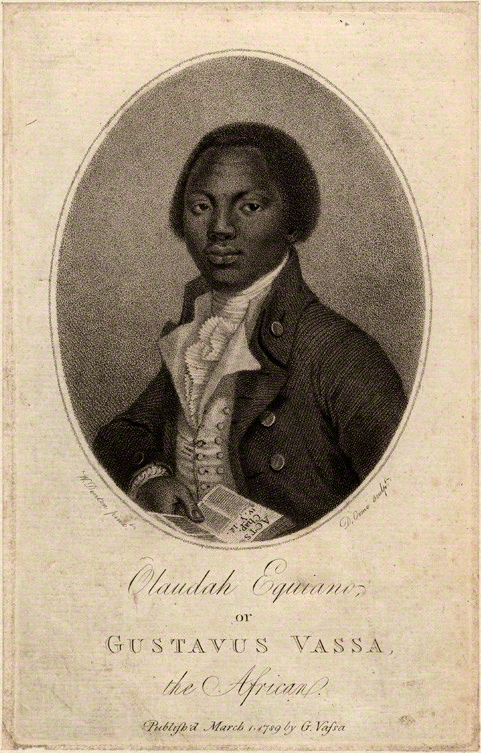

Ray Costello gives a longer history of race in Liverpool extending to the present day. And Vincent Carretta talks about the sometimes unpleasant aftermath to his discoveries about Olaudah Equiano.

It was a huge learning experience for me, but also tremendously rewarding to discover that all of these people, many of them unknown to each other, and others who knew of the others’ work but had never met them, are continuing to bring to light a past that is not past at all.

* Please be aware that right now Amazon appears to have sold out of copies and are not re-stocking at present due to the current COVID19 situation. However, copies of Gretchen’s book are available directly from her publisher Liverpool University Press. They are currently offering a 50% discount on all of of their ebooks as everything is becoming a little more digital at the moment. The discount code is EBOOKLUP

Fascinating post. Have you heard, perhaps, of my 6th great aunt, Margaret Gambier, c 1730-1789 who influenced the abolutionists? She married Adm Sir Charles Middleton. There is s portrait of her in NPG London with a good biography.

Sylvia

LikeLike

Thanks for the tip! I hadn’t heard of her, but just looked her up–it’s a fascinating story. http://solagratius.blogspot.com/2010/10/before-clapham-legacy-of-margaret.html

LikeLike

This is with regards an article on the portrait which the Guardian seriously botched when the film, BELLE, opened in London, but absolutely refused to do anything to help the writer, Stuart Jeffries, or myself rectify the situation.

https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2014/may/27/dido-belle-enigmatic-painting-that-inspired-a-movie

Six years later and I’m finally getting the hang of social media. This tweet which I started posting several months ago is basically the opinion piece I suggested to them at the time as an alternative and which they could either have published under my name or rewritten by one of their own reporters.

Because this painting is such a surprisingly early as well as humorously brilliant deconstruction of racial preconceptions, hope the media will be able to help flag it to the public desperate for any possible examples available of this kind of positive black imagery.

Besides the universal importance of her grand uncle, Chief Justice Mansfield’s 1772 decision which marked the beginning of the end of slavery in British North America, Dido Belle’s story also has a very personal purchase on our own nation’s history since her mother, Maria Belle, spent most of her life and presumably died here in Florida.

Last year, I stumbled across the recent re-attribution of the work to David Martin, a pupil of Allan Ramsay’s. Wondering why no one had ever explored this possibility, considering that the latter was Dido’s uncle, I am hoping this development is correct since it was from their studio that practically all of Queen Charlotte’s portraits playing up her “true mulatto face” were dispersed to the four corners of the world. Was the anachronism of his consort’s Negroid features on so exalted a dignitary, for instance, give George III the idea of having a “black” or “Moor” assume his own royal majesty at Sir John’s investiture, or, with the Indian sub continent by then already so much in the balance, did he see Charlotte’s appearance as potential PR in the early development of the British Empire? With more answers come more questions.

But all the more exciting, don’t you think?

Mario Valdes

Cambridge, Massachusetts, USA

LikeLike

A really interesting article, thank you. Have you heard of Joseph Antonio Emidy? I discovered him on one of my past trips to Falmouth, where there is a memorial to him at the Falmouth Parish Church of King Charles the Martyr.

LikeLike

Hello Penny, I don’t know of him in particular but there were many prominent musicians of African descent in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. I’ll make sure to add him to my list, as his story if great one, profiled by the BBC. One of the contributors to this book, Kathleen Chater, may well know of him, since she has an important database of black people in early Britain.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I mention Emidy in my book Untold Histories, Black People in England and Wales during the period of the British Slave Trade c. 1660-1807 (Manchester University Press, 2009). His story was first told by Richard McGrady in his study Music and Musicians in Early Nineteenth Century Cornwall (University of Exeter Press 1991). There are descendants in America and I think one of them has published a genealogy. Now, with the digitisation of newspapers and many other records there’s much more to be discovered.

Kathleen Chater

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, Kathleen, those will be going on my list!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Penny: In my chapter on black sailors I mention Joseph Emidy. Here is my database entry for Emily: “JOSEPH EMIDY aka JOSEPH EMEDE. The traditional story concerning Joseph Emidy, is that he was a Guinea-born violinist in the Lisbon opera house who was impressed in 1795 when the captain of HMS Indefatigable, having heard Emidy play and wanting the black to be part of his ship’s band, directed a lieutenant and several seamen to grab the young African when he exited from the theater. Emidy went on to serve almost five years in the Royal Navy before he was discharged as a free man in Falmouth in 1799. Jack Tar: Life in Nelson’s Navy, 334-5. A review of Royal Navy musters tells a slightly different tale. ¶ Emidy served on HMS Indefatigable. The ship’s muster indicates that Emidy (listed as “Joseph Emede”) entered man-of-war on October 1, 1795 as a “Volunteer” Landsman at Lisbon and that he entered the crew from the Supernumary List. This does not mean he had not been impressed; as Denver Brunsman has noted, the Royal Navy musters “did not make hard distinctions between forced men and volunteers.” Brunsman, The Evil Necessity, 6. In any event, Emidy served on the Indefatigable until March 15, 1799 when he was discharged onto HMS Impetueux as an able bodied seaman. While the Impetueux’s musters and pay rolls are unclear as to his exact date of discharge from the Navy, they do indicate Emidy remained on board HMS Impetueux as an Able Bodied Seaman through at least the last week of April, 1802. Thus, he had a more extensive naval career than is traditionally thought to be true. HMS Impetueux Musters, 1798-1804, ADM 36/12827, 36/12871-72, 36/15964; HMS Impetueux Pay Rolls, 1800-1802, ADM 35/851. C. Foy

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you, Gretchen and Charles. The information I have on Emidy is all from a one sheet article by Geoffrey J. Stobie, that I obtained on my visit to the church in Falmouth. He credits Galina Chester for the bulk of the information about Emidy. I understand that it was Edward Pellew (later Admiral) who initially pressed Emidy onto his ship Indefatiguable. Stobie mentions a benefit concert for Emidy at Wynn’s Hotel, Falmouth on 19th August 1802, containing a violin concerto composed by Emidy. He also says that at this time, Emidy was Leader of the Falmouth Harmonic Society, and that he married in September the same year Jenefer Hutchins — Emidy crammed quite a lot in, if he was only discharged from the Impetueux in April 1802!

My interest stems from my general research on Falmouth (for my fiction book) and general enthusiasm for discovering individuals who have been overlooked.

LikeLiked by 1 person