I first became acquainted with this gentleman when a good friend on social media messaged me with ‘I think this story needs you‘. Say no more, I was off down that rabbit hole. What a fabulous painting by John Dempsey of an early 19th-century gentleman from Norwich, but with no name apart from ‘Black Charley’ and nothing more known about him.

Black Charley, Norwich, 1823

The newspapers and parish registers came to the rescue in identifying this very dapper-looking man in his very smart clothing, who appears to have made and sold fashionable boots and shoes from a shop in Norwich, but perhaps looks can be a little deceptive.

The National Portrait Gallery of Australia (to whom the portrait was on loan to from Tasmanian Museum and Gallery), suggests that the gentleman may have been a child brought to England by Capt. (later Rear-Admiral) Frederick Paul Irby who had him baptised on 30 May 1813, as Charles Fortunatus Freeman, along with two other children and whilst this is feasible the dates don’t seem to tie up as you will soon find out.

Firstly, let’s give him the name by which he was known – may I introduce to you Mr Charles Willis Yearly of Norwich.

As yet nothing is known about where he was born, whether here in the UK or overseas, but from his burial, we now know that he was born around 1785 which arguably means that he was not the child baptised in 1813, as this would have made him around 28 at the time, so not a child. I still have no idea where the middle name ‘Willis’ came from.

On St Valentine’s Day 1820, Charles married Diana Norman of rural Stradbrooke, Suffolk, at the parish church of St Michael at Thorn, Norwich.

Despite his very dapper appearance, neither he nor Diana was able to sign the register and instead simply made their mark with an X, which leads me to think that perhaps these were more than likely second-hand clothes. The witnesses being Elisha Briggs, a farmer and landlord of The Two Necked Swan, Norwich and William H Houghton., who appears to be the second witness to all marriages around that date.

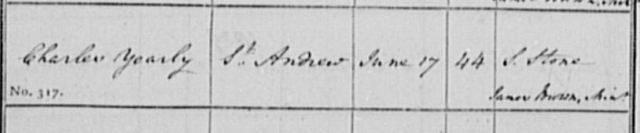

It was at the end of 1822, at the parish church of St Andrew’s, Norwich that the couple proudly presented their first son and heir, Charles Willis to be baptised. At the time Charles gave his occupation as being that of a ‘broker’, essentially a salesman, so not actually making the boots and shoes in the painting but selling them from his shop, these were second-hand boots and shoes.

The following year saw the arrival of a second child, again a son, Richard Willis, who died aged just two. The next birth was that of Jeremiah in 1825, followed by a daughter, Lydia in 1827.

At the end of 1828 things were not going well for Charles when he found himself in the House of Correction for assaulting a woman, this sentence being ‘three months on the treadwheel‘, which must have made life difficult for Diana as she was pregnant at the time with their final child who was born February 1829, a daughter, Mahalah.

It was then in 1829 that Charles was to die, aged just 44, and was buried on June 17 at St Andrew’s church. Given his sentence, it seems feasible that the time spent on the treadwheel may well have contributed to his demise (speculation of course).

His death was closely followed by that of his infant daughter, Mahalah, whose name appears on the same page of the burial register, but on the 31 December.

This left Diana to work out how to proceed as a widow with three children under 10 – Charles, Jeremiah and Lydia for comfort, but more importantly, to support if they were to avoid the workhouse.

The family business was taken over by a gentleman by the name of Mr Clarkson, who was described in the newspaper as

a dealer in old shoes, being the same colour and successor of a gentleman well known in Norwich by the title of Black Charley.

We meet up with Diana again on the 1841 census, the family had left their shop and moved to Black Horse Yard, Lower Westwick Street, in the St Lawrence district of Norwich.

Clearly, money was in short supply as Diana had become a washerwoman, but by now she had her three children all in their teens to assist with the household chores as well as being in employment. Her son, Charles was a labourer coachmaker, Jeremiah, a hawker, selling around the local area, the census doesn’t offer any clues as to what wares he was selling though. Lydia was just 13, so it would be safe to assume she was helping her mother until aged just 16, she was to die.

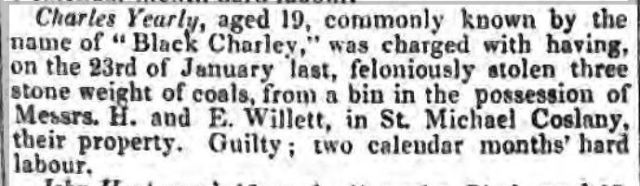

Quite what became of their son, Charles is a little unclear, but in 1842 he found himself in court a few times for theft.

In another newspaper report, Charles was described as ‘a mulatto son of Old Black Charley‘, thereby confirming that Charles and Diana’s marriage was a mixed-race marriage.

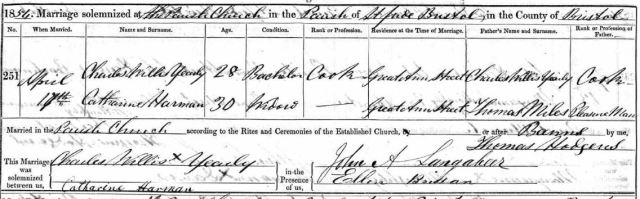

Young Charles Willis re-surfaced in Bristol when, in 1854 he described himself as a cook when he married a young widow, Catharine Harman. He named his father as Charles Willis, describing him as a cook – this is an occupation that doesn’t seem to have appeared anywhere else.

Being slightly suspicious, I do wonder whether he was being completely truthful when he married, especially as he also got his age wrong – he said he wasn’t born until 1826 when he was born 1822. Quite what happened with this marriage is lost to history right now, but curiously he appeared again in 1862, back in Norfolk where both he and his co-conspirator, John Harman were sentenced to a month in prison for larceny. Was John Harman connected to his wife Catherine, who knows, but it’s an unusual surname, so it seems likely. There is a burial for a Catherine Yearly in 1862 which in all likelihood was Charles’ wife.

Charles re-offended and found himself back in prison only a matter of weeks later, for a further six weeks.

Diana spent her remaining days living in Suffolk, with her son Jeremiah, his wife, Sarah, where at the age of 75, Diana was still working as a laundress.

In 1871, Jeremiah was a marine store dealer and by 1881 they had converted their home into a lodging house – 6, Mariners Street, Lowestoft where they remained until the end of their lives. Jeremiah was buried on 10 June 1886, aged 65, at Lowestoft, just two years after his wife Sarah Ann and as the couple had no children, with their death the Yearly name died out unless any proof appears that young Charles had any children, although that seems unlikely.

It would appear from the 1871 census that Diana was living at the House of Industry, Oulton, Suffolk, incorrectly named as Eliza Yearly, but with her age and place of birth being correct. She died there, aged 90 in 1879.

Sources

National Portrait Gallery, Australia

Norfolk Public houses

Norwich Mercury 10 April 1830

Norfolk News 15 February 1862

Parish Registers Norwich

Criminal Registers Norwich

Featured Image

The Old Fish Market, Norwich. Charles Hodgson (1769–1856) (attributed to). Norfolk Museums Service

Hello Sarah,

I hope you’re self-isolating and taking this all seriously! I have been at home for a week and a half, although twice I went for a walk and my husband has gone out for groceries a few times. One of our sons lives in Brooklyn with his wife and two children, and since NYC is now an epicenter the kids are being schooled “virtually.” We also have Italian passports, so truly there is no place to hide.

Now, about Black Charly. What a great post, and right up my street. I wanted to mention that it was not at all uncommon for black people in Britain to be baptized as adults, particularly if they had been enslaved. Many who arrived immediately got themselves baptized because they (mistakenly) believed that it conferred freedom on them in perpetuity. You don’t know whether Charles was born in England or was brought to England, but I’ve run across lots of mentions of black adult baptisms. I’m sorry though that he and his family came to such bad ends, no doubt caused by poverty and desperation.

On another note, I got a Liverpool UP alert about the book and it looks as though it publishes on March 31. It even has a link to my BBC Radio 4 series from a few years ago. I’ll forward it to you. However, I’m swamped with trying to run a large college in a large university from home—I have videoconferences beginning in half an hour—so can’t get to the post yet, but will let you know.

Best

Gretchen

From: All Things Georgian Reply-To: All Things Georgian Date: Wednesday, March 25, 2020 at 6:09 AM To: Gretchen Gerzina Subject: [New post] Portrait of ‘Black Charley of Norwich’ by John Dempsey

Sarah Murden posted: “I first became acquainted with this gentleman last week when a good friend on social media messaged me with ‘I think this story needs you’. Say no more, I was off down that rabbit hole. What a fabulous painting by John Dempsey of an early 19th-century ge”

LikeLike

Hi Gretchen

Thank you, I am staying safe and plan to keep it that way.

Charly – it’s not impossible that the baptism that appears in the parish register of 1813 was his, but the 3 children Captain Irby had baptised were ‘boys’ and by 1813 Charly would have been 28 unless he got his age wrong by perhaps 10 years. I have to say he does look very young in the portrait, so it seems feasible that he got it wrong. I can’t find any evidence of a definitive baptism for him here in the UK, so it’s a mystery as to where/when he arrived.

I’ll catch up with later about the book.

LikeLike

Hello Sarah,

I’m very interested in your post, as I too have come across Captain Irby of Boyland Hall, near Norwich, and Charles Fortunatus Freeman. In 1815 the Norwich painter Michael William Sharp exhibited at the Royal Academy a ‘Portrait of a British officer, delivering an African slave whom he brought to England, and is now at his seat in Norfolk.’ (I’ve yet to locate this painting, which is my main quest).

A print issued in 1813 has a long explanatory text added to it, where Charles Fortunatus Freeman’s redemption from slavery is recounted. See

https://www.rmg.co.uk/collections/objects/rmgc-object-254373.

For Freeman’s story, I’d loosely imagined the print as the ‘before’, Sharp’s painting as the ‘middle’ and Dempsey’s portrait as the ‘after’ but your post questions that neat assumption. The representation of the boy in the print (‘drawn by an officer’, so perhaps by Irby himself) is pretty ambiguous about age but still shows a teenager I think. So unless the death certificate wrote ’44’ by mistake for ’34’ I think we have to accept your conclusion that ‘Black Charley’ is Charles Willis Yearly rather than Charles Fortunatus Freeman. (But what happened to Freeman, I wonder?)

If you have any further light to throw on all this I’d be glad to hear of it.

Kind regards,

Sam

LikeLike

Thank you for your comments. I honestly don’t feel that Black Charley of Norwich looks anything like the boy in that print, even allowing for the increase in years, but as to what became of Charles Fortunatus Freeman, I have absolutely no idea, he is still in my cross hairs though in case something turns up. I had hope Frederick Paul Irby’s will might give some clues, but to say it was short is an understatement – ‘everything to my wife, Frances and children’!

LikeLike

Amazing detective work, Sarah. What a fascinating family, and an example of all the ways people tried to make a living of some sort to avoid the workhouse (apart from the bad apples, of course!)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much Penny for your comments 🙂

LikeLike

A sad tale of the hard life led by this Norwich man. The city has, of course, a more illustrious C19 black inhabitant in Pablo Fanque, the circus owner celebrated by The Beatles.

(PS the church in which Charles and Diana were married is St Michael at (not and) Thorn)

LikeLike

Yes of, Pablo Fanque – another fascinating story. St Michael – typo amended – my mistake 🙂

LikeLike

Wonderful stuff, Sarah, and a good reminder that Britain was more diverse than is sometimes appreciated. It is likely that Charley’s descendants are completely unaware of their heritage.

LikeLike

Thank you so much Naomi, it was great to be able to put a little ‘flesh on the bones’.

I’m not sure there were any descendants. When Diana died there were just 2 sons remaining – Jeremiah and his wife didn’t have any children. Young Charles and his wife don’t appear to have had any either. The only mystery person remains John Harman, who may possibly have been Catherine’s son by her first husband, in which case he still wouldn’t be part of the Yearly clan.

LikeLike

Wow, something else to see someone else researching the same person from nearly

two centuries ago across the ocean. I was researching his last name hoping to find an

African name, I was also very puzzled by the boots and shoes around the door. Now I know both, Thanks to you. I will most likely display the image displaying fashion on African descended

generations in the Atlantic Diaspora. Mr. Charley will fall in the Sixth generation 1625-1649.

LikeLiked by 1 person