Today we have the final part of the story about General James Wolfe, so I’ll hand you over to Kim to complete this and take this opportunity to say a massive ‘Thank You’ to Kim, for all her hard work in writing this fascinating story.

If by any chance you missed any of the first 3 parts, click on the following links – Part 1; Part 2; Part 3.

Events moved quickly, and not only in Wolfe’s professional life.

Her name was Katherine Lowther, and she was his parents’ “pretty neighbour” at Bath, whose sleep he had apologised for disturbing by his clattering departure one winter morning two years before. Her pedigree was impeccable: her father had been a governor of Barbados; one of her grandfathers was a baronet, his wife the daughter of a viscount; her sister was the Countess of Darlington. It was not the coup de foudre which had shattered Wolfe’s life in 1749 and he said he had “no thought of matrimony”, but there was clearly commitment; and he took his final leave of his parents by letter, claiming that he disliked the emotional business of parting. Henrietta Wolfe remained jealous and suspicious, and Lieutenant-General Edward Wolfe altered his will, leaving his considerable estate to his wife with no provision for his son.

Wolfe learned of this in Louisbourg in May, following a rough passage in H.M.S. Neptune to New York, and from there to a fogbound Halifax, the harbour of which was still choked with ice. Edward Wolfe’s death in March had not been unexpected, as “I left him in so weak a condition that it was not probable we should ever meet again”, but the financial blow was a heavy one, although he wrote to Henrietta from “the Banks of the St. Lawrence, 31st August 1759… I approve entirely of my father’s disposition of his affairs, though perhaps it may interfere a little matter with my plan of quitting the service, which I am determined to do at the first opportunity⸺ I mean so as not to be absolutely distressed in circumstance, nor burdensome to you or anyone else.”

He had made his will aboard Neptune, leaving to Katherine the miniature she had given him, “to be set in jewels to the amount of five hundred guineas, and returned to her.”

Perhaps the future would always be only this: an endless repetition of the past. A flirtation with life, the certainty of death, an evanescent dream.

He disposed, generously, of his other assets, and his aides witnessed his signature. There was nothing else, nothing more. The rest, even she, was an illusion.

***

He burned his personal journal for August, with its bitter catalogue of affront, resentment, suspicion, foreboding and depression, and its accounts of “a sad episode of dysentery”, not now uncommon in an army encamped in extreme heat and humidity, and increasingly severe bouts of renal colic. He had asked for something to ease the pain, fearing that events would slip beyond his control and that he would be unable to prosecute this final attack on a tenacious and unaccommodating enemy.

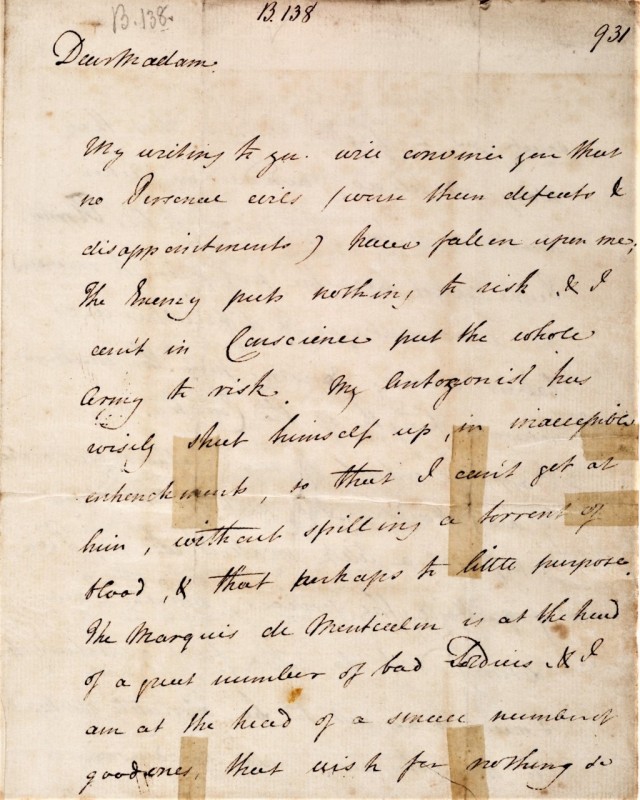

My antagonist has wisely shut himself up in inaccessible entrenchments, so that I cannot get at him without spilling a torrent of blood, and that perhaps to little purpose. The Marquis de Montcalm is at the head of a great number of bad soldiers, and I am at the head of a small number of good ones, that wish for nothing so much as to fight him; but the wary old fellow avoids an action, doubtful of the behaviour of his army. People must be of the profession to understand the disadvantages and difficulties we labour under, arising from the uncommon natural strength of the country.

Rumours of his illness had disconcerted men already unnerved by a summer of skirmishes and scalpings and sniping by disaffected habitants bearing arms and grudges against the British.

The French did not attempt to interrupt our march. Some of the savages came down to murder such of the wounded as could not be brought off, and to scalp the dead, as their custom is… Scarce a night passes when they are not close upon our posts, watching an opportunity to surprise and murder. There is very little quarter given on either side.

It revolted him. His orders of the 24th of July read: “The General strictly forbids the inhuman practice of scalping, except when the enemies are Indians or Canadians dressed as Indians,” but a subsequent order posted a bounty of five guineas for an aboriginal scalp. The Canadians were offering a similar reward for a British scalp, and after a Captain Alexander Montgomery of the 43rd Foot found his brother’s body “cruelly mutilated by the savages” he had reciprocated in a manner they understood: he and his men had murdered and scalped a priest and twenty of his congregation when they had refused to disarm in St. Joachim on the 23rd of August.

In every man of every race the creed of the frontier, the inner savage, was asserting itself.

No churches, houses or buildings of any kind are to be burned or destroyed without orders. The persons that remain in their habitations, their women and children are to be treated with humanity. If any violence is offered to a woman, the offender shall be punished with death. If any persons are detected robbing the tents of officers or soldiers they will be, if convicted, certainly executed. The commanders of regiments are to be answerable that no rum, or spirits of any kind, be sold in or near the camp.

But it was the enemy within he hated: not Montcalm, not the Canadians, not the Iroquois Confederacy, but a confederacy of his own brigadiers, sworn to subvert, discredit and undermine his authority.

His right to choose his own staff officers had been a condition of his acceptance of command, and he had thought he knew them: his aides, Captains Hervey Smith and Thomas Bell, remained loyal and protective of him.

An Irish major named Isaac Barré was adjutant-general: he had not yet betrayed Wolfe’s trust. The others were his quartermaster-general Lieutenant-Colonel Guy Carleton, an Irish veteran of Flanders whose commission for Louisbourg the King had refused to sign because Carleton had insulted the Hanoverians: even Carleton, a friend, had offended Wolfe by his “abominable behaviour”; the Honourable Robert Monckton, brigadier-general commanding the first battalion, who had been lieutenant-governor of Nova Scotia and had overseen operations in the Bay of Fundy after Louisbourg; and the Honourable James Murray, brigadier-general commanding the third battalion, a touchy Scot whose brother was a known Jacobite, and who had served in Flanders and at Rochefort and Louisbourg. He was increasingly influenced by Colonel the Honourable George Townshend, honorary brigadier-general in command of the second battalion. Townshend had been Pitt’s choice, not Wolfe’s. He had fought in Flanders and at Culloden, been aide-de-camp to Cumberland and then to George II, and was called by Horace Walpole “proud, sullen and contemptuous”. He was also a maliciously talented cartoonist and had satirized Cumberland to the detriment of his own career. He now found in Wolfe both subject and target and was circulating with impunity his caricatures of ‘Our General’, hinting that Wolfe’s judgment was clouded by opium and that his refusal to disclose his plan of attack was indecision or, at worst, paranoia.

Wolfe was, by his own admission, “so ill and so weak that I begged the General Officers to consult together for the public utility and advantage; and to consider of the best method of attacking the enemy.” He offered them what he called “a choice of difficulties”. They rejected all three options and mooted one of their own, Townshend claiming afterwards that Wolfe had never had any intention of forcing a pitched battle at Quebec.

For a man who was bluffing or indecisive, or too ill or too drugged to function, his mind remained exceptionally focused, detailing the siting and calibre of artillery, and designating specific ships, batteries, and signals; collating information from every source including deserters, whom he questioned himself; conducting solo reconnaissances on foot or by boat; noting the dispersal of Montcalm’s forces, the Duc de Lévis somewhere between Quebec and Montreal with an army of 4,000 chosen men, Colonel Louis-Antoine de Bougainville at Cap-Rouge with another 3,000 regulars, militia and aboriginals; reading the reports of shortages and damages within the city; considering the logistics: the immutable, the inalienable, the impossible. He knew every officer and had trained and drilled personally many of the men: the combined forces were now a weapon poised to strike when the time and the tide and the peculiarities of the river and the phase of the moon dictated. He had seen the place in early July and had conferred with the navy’s navigators and cartographers, among them James Cook. The time was now.

Those commanders he trusted he briefed in full, including the navy, with which close co-operation was vital. He issued his final orders on the afternoon of September 12th, from aboard H.M.S. Sutherland.

The enemy’s force is now divided; great scarcity of provisions is in their camp and universal discontent among the Canadians. The second officer is gone to Montreal or St. John’s, which gives reason to think that General Amherst is advancing into the colony. A vigorous blow struck by the army at this juncture may determine the fate of Canada. Our troops below are in readiness to join us; all the light artillery and tools are embarked at Point Levi, and the troops will land where the French seem least to expect it.

The first body that gets onshore is to march directly to the enemy and drive them from any little post they may occupy. The officers must be careful that the succeeding bodies do not by any mistake fire upon those who go before them. The battalions must form on the upper ground with the expedition, and be ready to charge whatever presents itself. When the artillery and troops are landed, a corps will be left to secure the landing-place, while the rest march on, and endeavour to bring the French and Canadians to a battle. The officers and men will remember what their country expects from them, and what a determined body of soldiers, inured to war, is capable of doing against five weak French battalions mingled with disorderly peasantry. The soldiers must be attentive and obedient to their officers, and the officers resolute in the execution of their duty.

At 8:00 p.m., as the troops were climbing down into Sutherland’s boats, he received a letter signed by all three brigadiers demanding further clarification. Security was necessary, they conceded, but they had not been taken fully into the General’s confidence, and their orders were not specific.

He wrote to Monckton:

My reason for desiring the honour of your company with me to Gorham’s Post yesterday was to show you, as well as the distance, would permit, the situation of the enemy, and the place where I meant they should be attacked. The place is called the Foulon, distant upon two miles or two and a half from Quebec… as several Ships of War are to fall down with troops Mr Holmes will be able to station them properly after he has seen the place… The officers who are appointed to conduct the divisions of boats have been strictly enjoined to keep as much order and to act as silently as the nature of the service will admit of. It is not usual to point out in the public orders the direct spot of our attack, nor for any inferior officers not charged with a particular duty to ask instruction upon that point. I had the honour to inform you today that it is my duty to attack the French army. To the best of my knowledge and ability, I have fixed upon that spot where we can act with the most force and are the most likely to succeed. If I am mistaken, I am sorry and must be answerable to his Majesty and the public for the consequences.

To Townshend, controlling his dislike, he wrote:

Brigadier-General Monckton is charged with the first landing and attack at the Foulon, if he succeeds you will be pleased to give directions that the troops afloat be set on shore with the utmost expedition, as they are under your command, and when 3,600 men now in the fleet are landed I have no manner of doubt but that we are able to fight and beat the French army, in which I know you will give your best assistance.

To Murray, who was under Monckton’s command, he wrote nothing.

At 2:00 a.m., time and tide ebbing, Sutherland’s barge took the lead.

***

On the right of the line to the edge of the cliffs, with Wolfe in personal command, the 35th, the Louisbourg Grenadiers, the 28th, the 43rd. In the centre under Monckton, Lascelles’, the 47th: Scots who had fought Scots at Prestonpans and Culloden. On the left, Murray with the 78th, the Fraser Highlanders, born, perhaps, of a conversation one evening in Inverness between Wolfe and Simon Fraser, whose father, the Jacobite Lord Lovat, had been beheaded for treason in 1747. Fraser had been out with his clan for the Pretender in the ʼ45 and been pardoned in 1750. Wolfe had suggested he raise a regiment for the King, and the Frasers were here now, bristling with the weapons the Disarming Act of 1746 still forbade civilians to carry in Scotland. They were, he acknowledged, among the finest soldiers he had ever known. Beside them, Anstruther’s; and in the second line, where Townshend could do the least damage, the 15th and two battalions of the 60th. In reserve, Lieutenant-Colonel Ralph Burton’s 48th in eight sub-divisions; and at the rear Colonel the Honourable William Howe, another friend of Wolfe’s, with the rangers and light infantry.

The French colours surrendered at Louisbourg had been paraded in London and put on display in St. Paul’s Cathedral. He did not want to see these six-foot standards, the King’s colours and these regiments’, so dishonoured in Paris.

Daybreak: just after 5 a.m. The rain fell. They waited, unmoving. The ‘plains’ were fairly level, but patched with cornfields and studded with undergrowth and coppices that afforded cover to native and Canadian marksmen. The French picquets, running, had reached Quebec with intelligence that the entire British army was established on the heights to the westward, on, Montcalm noted, “the weakest side of this miserable garrison,” and had, by their presence, thrown down a psychological gauntlet no soldier of honour could ignore.

By 7 a.m., in showery rain, the French were seen coming out, one eyewitness reported, “like bees from a hive”. Sniping by Canadian irregulars and their aboriginal allies intensified. The French opened fire with artillery, and the hailstorm of lead from the Canadians became “very galling”: rather than sacrifice men’s lives prematurely, Wolfe ordered the infantry to lie down briefly in their ranks. The French formed three columns, some 7,500 men, and at about 10 a.m. began to advance. The thin red lines waited.

Apprȇtez vos armes… En joue… Feu!

From his position on the right, on slightly rising ground, Wolfe observed. A soldier wrote later, “I shall never forget his look. He was surveying the enemy with a countenance radiant and joyful beyond description.”

A bullet tore the tendons of his right wrist. He tied it up with his handkerchief: it seemed to cause no pain. The fire was very hot now from the sharpshooters: he could handle a fusil as well as any sergeant and he tore the cartridge with his teeth and spat out the fragment, and waited; every musket in the line was double-shotted on his orders. Amongst the French, there were shouts: obscenities, jeers, encouragement, shouts of Vive le Roi! and Marquez bien les officiers! And marked they were, in the oblique fire from the Royal Roussillon, the Compagnies Franches de la Marine, the battalions of La Sarre, Languedoc, Béarn, Guyenne: Monckton shot in the chest, his left lung collapsing, Carleton sustaining head wounds, Barré’s nose and left cheekbone smashed by a musket ball, his left eye blinded.

They took it, standing impassively with shouldered arms. One hundred and forty yards: one hundred and twenty. The French had four or five field guns: they had hauled only two up the cliffs. A hundred. Hold your fire. Eighty. Sixty. Hold your fire, damn you. At forty yards, on the command, they opened fire: a single volley in unison, which had the effect of a cannonade. When the smoke cleared the plain was littered with greyish-white uniforms, stained scarlet: the dead, the dying, the mutilated. They fired another five volleys. It was 10:15 a.m. and the sun had come out, glinting on bayonets. From further along the line there was a hiss of drawn steel as the Highlanders unsheathed their broadswords.

A quarter-inch of metal, a bullet or shrapnel from an exploding shell, hit Wolfe in the groin: they were under heavy fire from the front and flank, and he was too conspicuous a target to ignore. He waved his hat, signalling that the whole line should advance; and then two bullets pierced his left breast, and he staggered and almost fell. He was caught, supported. “Hold me up,” he said, “don’t let my brave fellows see me fall.” He leaned on Captain Ralph Corry of the 28th, and then there were others: Lieutenant Henry Browne of the Louisbourg Grenadiers, a volunteer named James Henderson, another officer: blue uniform, red facings. Artillery. He tried to help them, but his strength and his vision were failing: he collapsed, and they carried him through the smoke another hundred yards to the rear. Henderson held him upright while Browne tore at his waistcoat, and saw that his shirt was soaked with blood. He attempted to dress the wound, but the haemorrhage could not be staunched. He asked if Wolfe wanted a surgeon.

“No need,” he said, “it’s all over with me.”

Someone else, a grenadier, was shouting.

“They run! See how they run!”

He stirred, rousing himself, they said afterwards, like a man from a heavy sleep. “Who run?” he said, and the grenadier, shocked by what he was witnessing, answered, “The enemy, sir. Egad, they give way everywhere.”

One more order, and then there would be peace. He said, “Take a message to Colonel Burton. Tell him to take Webb’s with all speed to Charles River, to cut them off before they reach the bridge.”

And then to Browne, whose arms were around him, “Lay me down. I am suffocating.” Browne, crying openly, laid him gently on the ground, and cradled him as he died.

***

He had been greatly loved, far more than he had known. Browne wrote to his father: “Even the soldiers dropped tears, who were in the minute before driving their bayonets through the French. I can’t compare it to anything better, than a family in tears and sorrow which had just lost their father, their friend, and their whole dependence.” Lieutenant-Colonel Alexander Murray of the Louisbourg Grenadiers wrote to his wife, “His death has given me more affliction than anything I have met with, for I loved him with a sincere and friendly affection.”

His body was carried from the field wrapped, it was said, in a plaid offered by a wounded Highlander, and brought aboard the 28-gun frigate H.M.S. Lowestoft at 11 a.m. It was embalmed, and eventually placed in a stone sarcophagus taken from the convent of the Ursulines, which had been heavily damaged by bombardments from the batteries at Pointe aux Pères: Montcalm was buried there at 8 o’clock on the evening of the 14th in an enlarged shell hole in the floor. Quebec capitulated on September 18th. Montreal fell a year later.

News of the victory reached England on October 17th and the country went wild with bonfires and celebrations, although friends and neighbours in Blackheath refused to illuminate their houses out of respect for James’s memory, and his mother’s very real grief.

Wolfe’s body, brought home aboard the 84-gun H.M.S. Royal William, arrived at Spithead at 7 a.m. on the morning of Saturday, 17th November. The raucous port he had called “this infernal den” was hushed as Royal William’s barge, escorted by others and to the sound of tolling bells and muffled drums, conveyed the sarcophagus to Portsmouth Point. Now transferred to an oak coffin and accompanied by Captains Thomas Bell and William De Laune, it was placed in a hearse and driven to Blackheath. It had been discovered on opening the sarcophagus that the face had decomposed too much to allow a death mask to be made: the sculptor Joseph Wilton modelled his commemorative marble bust on a servant thought to resemble Wolfe. He was advised by Richard, second Baron Edgcumbe, a draughtsman and patron of the arts who had known Wolfe and was able to recreate the beaky, angular features to an almost forensic degree.

Wolfe’s coffin, covered with a pall of black velvet and heaped with laurels, lay in state at his mother’s house the night before a private funeral on November 20th at the church of St. Alfege in Greenwich. There were five mourners, all male. Henrietta Wolfe remained prostrate with grief and did not attend.

She petitioned the government unsuccessfully for Wolfe’s pay to be increased to parity with Amherst’s, and “for a pension to enable me to fulfil the generous and kind intentions of my dear lost son”, which she said she could not otherwise honour “without distressing myself to the highest degree.” She did, however, pay the jeweller Philip Hardle £525, and returned the miniature, set with diamonds, to Katherine Lowther as Wolfe had requested. Katherine wrote to her but dared not call on her.

Your displeasure at your noble son’s partiality to one who is only too conscious of her own unworthiness has cost her many a pang. But you cannot without cruelty still attribute to me any coldness in his parting, for, madam, I always felt and express’d for you both reverence and affection, and desir’d you were ever first to be considered.

They never met again.

Henrietta Wolfe died on September 26, 1764, and was interred between her son and her husband in the family vault in the church of St. Alfege. Katherine Lowther married Vice-Admiral Harry Powlett, later the sixth Duke of Bolton, on April 8, 1765. Wolfe’s letters to her and those she wrote to him at Quebec, which arrived too late and were returned to her unopened, have not survived. She died in 1809.

In England, he is all but forgotten. In Canada, the tides of political correctness alternately burnish and tarnish his reputation. The vast, untamed country of which he said “every man is a soldier” is now dedicated to peacekeeping; bears and beavers still roam the wilderness; and the snow, falling early and lingering long, still, in the true north, covers the ground for eight months of the year.

I went to the National Army Museum last week, and there was a banner outside showing Wolfe. I was able to impress my friends with my knowledge of who he was, thanks to you! Very informative articles, thank you.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Oh, how fabulous, Kim will be thrilled to hear that, I’m sure 🙂

LikeLike

I’m absolutely delighted! Wolfe would be pretty chuffed, too. Thank you, Sylvia, and to dear Sarah for the opportunity to bring him to life here on “All Things Georgian”.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Very glad to read Gen.SimonFraser gets a mention here,his 78thHighlanders.It also shows a link

With Gen.Wolfe as friends.Fraser was yet to raise another regiment of Highlanders years later and handed over to ArchibaldCampbell for his SavannahCampaign—they were relatives.Fraser

along with SirJohnLindsayKB were witnesses at Campbell’s wedding in July1779 and all were

Scottish,unlike Wolfe who was English.

Simon died in 1782,SirJohn in 1788 and SirArchibald in 1791 and they all served their country,

even though a wee bit of the Jacobite was within them after all those years.

Well done Kimberley for a detailed read and keep watching this blog for intriguing finds in the

near future!

Etienne P.Daly:Researcher On DidoElizabethBelle.

LikeLike

There was so much of Wolfe’s life, including the years he spent in Scotland, and his relations with the Highlanders in particular, that I had to omit for reasons of space. As a novelist with a special interest in the British army of the 18th century and in the Jacobite rebellion of 1745, I found it all fascinating and deeply moving. I’m so glad you enjoyed my post.

LikeLike

Thank you for this story Kimberly reeman

LikeLike

You are most welcome.

LikeLike