Which is exactly what happened in this case.

Edward Weld, son of Humphrey Weld and Margaret Simeons of Lulworth Castle was taken to court by his wife the Honourable Catherine Elizabeth, daughter of Lord Aston.

The couple married June 22, 1727, but according to Catherine, her husband was impotent. The trial took place in 1732. The couple had lived together for the vast majority of their marriage, but Catherine confirmed that the marriage was never actually consummated. Edward acknowledged that she was ‘able, apt and fit for the procreation of children’.

At this point Catherine decided that they could no longer cohabit; Edward’s view, however, was, that ‘many married people live together like brother and sister’. The couple were Catholic and as such deemed marriage to be as sacrament. Edward confirmed to Catherine’s father that it was true, the marriage had not been consummated, the reason for this being that he had ‘an outward defect which prevented him from consummation‘. Catherine’s father recommended that Edward visit a doctor who he felt sure would be able to quickly remedy this problem.

Three midwives were produced:

…that they are all well skilled in the art and practice of midwifery, and have very carefully and diligently inspected the private parts of the Hon. Catherine Elizabeth Weld, which are naturally designed for carnal copulation; and that to the best of their skills and knowledge she is a virgin and never had carnal copulation with any man whatsoever.

Depositions on behalf of Edward were made:

Edward Weld Esq. deposed, that he was of the age of 26, and has all the parts of his body which constitute a man perfect and entire, more particularly those parts which nature formed for the propagation of his species and the act of carnal copulation, in full and just proportion and was and is capable of carnally knowing Catherine Elizabeth Weld, his wife, or any other woman. And during the time he cohabited with his wife, his private member was often turgid, dilated and erected, as was necessary to perform the act of carnal copulation; and that he did as such time consummate his marriage by carnally lying wit and knowing his wife.

Mr Williams, an eminent surgeon, deposed that Mr Weld came to him in June 1728 and that upon examining his penis, he found the frenulum too straight, which he set at liberty by clipping it with a pair of scissors, and on examining that part again the next day, found nothing amiss in the organs of generation.

Five surgeons carried out an inspection of Edward too and agreed that he was perfectly capable of carnal copulation.

Having heard all the evidence, in a nutshell, Catherine Elizabeth was told to return to her husband and, in effect, to ‘put up and shut up’ the wording being that she should ‘remain in perpetual silence’. It was a decision which many felt at the time was cruel and unjust. In order to save face, Edward decided to counter-sue Catherine for libel and won but could not remarry until Catherine died in 1739.

Edward died in 1761 and his will dated April 17, 1755, makes for interesting reading as he left the majority of his estate to his son, Edward (born 1741), with other beneficiaries named as his second son John (born 1742), third son Thomas (born 1750) and daughter Mary (born 1753).

So, was the marriage eventually consummated? Presumably not, for after Catherine’s death Edward went on to marry Mary Theresa Vaughan (who died 1754) with whom he had the above-named children.

June 12, 1773, Edward Weld’s son, Edward wrote his will. He made reference to his late wife, the Honourable Lady Juliana (who died 1772) and left everything to his brother Thomas. His will was proven November 7, 1775, just after he died from a fall from his horse and only four months after he married Maria Smythe (married July 13, 1775, at Twyford, Hampshire), who was later to become Maria Fitzherbert, the secret wife of the future King George IV but, as Edward Weld junior didn’t have chance to update his will, Maria was left with nothing at his death.

I love little stories like this from the past. It gets your imagination going, wondering what the real story was! Unfortunately, the women always seem to come off worse than the men! Thanks for sharing 🙂

LikeLike

Delighted you enjoyed it, all we’re left with are the court records, so we’re left to draw our own conclusions about the truth!! 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

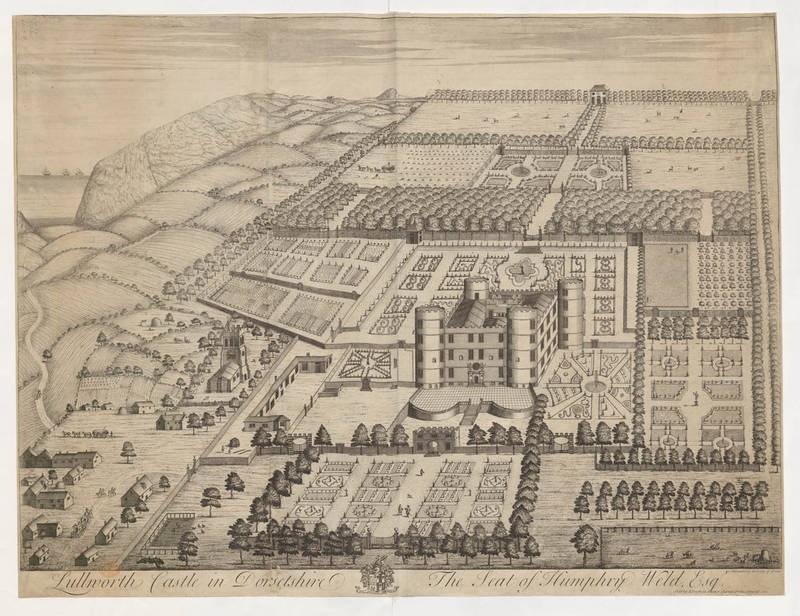

There is so much interesting history surrounding Lulworth. I am wondering where you picked up the drawing of the estate? My interest is in ancient Lulworth. My web site is: http://www.worldwidenewburghproject.com

LikeLike

We came across the image in the George III Collection, courtesy of SPL Rare Books, there’s a link to it at the end of the article which will take you straight to it. 🙂

LikeLike