Today we are honoured to be handing the reins over to a very special guest, the esteemed Dr Jacqueline Riding, art historian. Amongst her many credits she was the research consultant for Mike Leigh’s award-winning film Mr. Turner (2014) and is now working on his next feature film Peterloo.

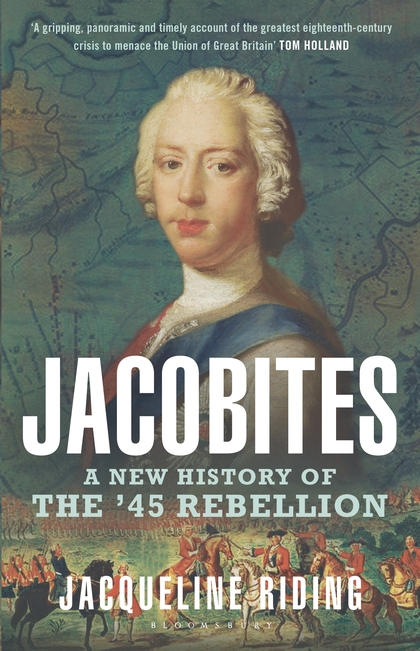

Her book Jacobites: A New History of the ’45 Rebellion has just been released by Bloomsbury Publishing. As a bonus, at the end of her article there is a competition to win a personally signed copy of her beautiful new book. So, without further ado, we’ll leave Jacqueline to tell you more.

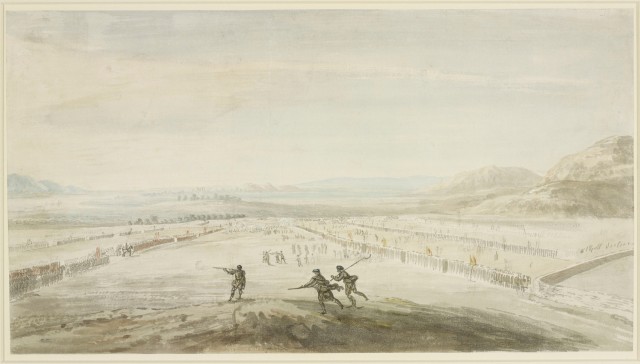

The recent commemorations for the 270th Anniversary of the Battle of Culloden (16th April 1746), the last battle fought on the British mainland, and the phenomenal success of the TV series Outlander, have certainly brought the 1745 Jacobite Rebellion back into the news, as well as the broader public consciousness. This, in turn, has generated an interest in discovering the history behind Diana Gabaldon’s popular novels (the inspiration for the TV drama).

Over the centuries, many books have been written on the ’45 that could be described, broadly speaking, as either pro-Jacobite or pro-Hanoverian: the former vastly outnumbering the latter. But in recent years there has been a desire among established and emerging scholars alike, to present this extraordinary moment in British history in all its complexity, and to place it, correctly, in an international, as well as national and local context. In this spirit, my book, Jacobites, straddles different disciplines, blending military, social, political, court, cultural and art history, and shifts, chapter by chapter, between an international setting, to the national, regional and local: from the battlefields of Flanders and the Palace of Versailles, to the Wynds of Auld Reekie and the taverns of Derby.

I also based the narrative, as far as possible, on first person or primary accounts – letters, journals, diaries and newspapers – through which the reader discovers what was known, or believed, by individuals or groups, at the moment the action or event is occurring. Vital to this was the year and a half I spent working on the Stuart and Cumberland Papers, the private papers of the exiled Stuarts and William Augustus, Duke of Cumberland (commander-in-chief of the British army at Culloden), both in the Royal Archives at Windsor Castle. The book’s style is often, therefore, closer to reportage and current affairs, than a retrospective history. In this way I aimed to avoid the overwhelming sense of romantic doom that tends to envelop ‘Bonnie Prince Charlie’ and the ’45, while, hopefully, keeping the reader in the moment: after all, in the years 1745-6, nothing was certain.

To whet your appetite, here is a quick introduction to the ’45.

In 1745 Charles Edward Stuart (b.1720) had one key aim: regaining the thrones his grandfather, the Roman Catholic convert James VII of Scotland and II of England and Ireland, had lost in 1688-90 to his protestant nephew and son-in-law William of Orange, who reigned as William III with James’ eldest daughter, Mary II. This ‘Glorious’ Revolution confirmed a Protestant succession in a predominantly protestant Great Britain, which, from 1714, was embodied in the Hanoverian dynasty.

Following George I’s accession, several armed risings in support of the exiled Stuarts occurred, most notably in the years 1715 and 1719, and Jacobite (from the Latin for James ‘Jacobus’) plots continued to plague the new Royal Dynasty. By this stage, on the death of James VII and II in 1701, the chief claimant, the ‘Old Pretender’ (from the French for claimant ‘prétendant’) was his only legitimate son, and father of Charles, James Francis Edward (b.1688). A major French invasion of Britain in support of the Stuarts in early 1744 had been abandoned, mainly due to severe weather, leaving Charles, who had arrived in France to lead the invasion, kicking his heels in Paris.

A year on, having understandably lost patience with his chief supporter and cousin, Louis XV, and with the greater part of the British army fighting in Flanders against the French, leaving Great Britain largely undefended, Charles secretly gathered together arms and a modest war chest, and set sail from Brittany, landing a small party at Eriskay in the Outer Hebrides on 23rd July 1745. His audacious – or reckless – plan was to gain a foothold in the Western Highlands, rally support en route south via Edinburgh, meet up with a French invasion force at London, remove the Hanoverian ‘usurper’ George II (r.1727), and then settle in at St. James’s Palace, while awaiting the arrival of his father, King James VIII and III. And while luck and the element of surprise were on his side, for a time it proved almost as straightforward as that…

To find out more you will of course need to read the book, but in the meantime here is a chance to win your very own copy.

The question Jacqueline has devised is for you is to tell us

Who is your favourite rebel and why?

There is no right or wrong answer and you don’t need to provide your address as we’ll email the lucky winner. The rebel can be from any period of history.

How to enter

Please reply to this post using the ‘Leave a Comment’ at the end of the post.

The Rules

All entries must be received by midnight on Tuesday 17th May 2016. The competition is open to readers in the UK only (prize courtesy of the publisher).

Good luck!

THE COMPETITION IS NOW CLOSED.

THE WINNER HAS BEEN NOTIFIED AND WE WOULD LIKE TO THANK EVERYONE WHO ENTERED.

The question does not make it clear whether this is a rebel, generally, or a rebel of the Jacobite risings. My favourite rebel of all time is Budic of the Iceni, [Boudicea] who very nearly humbled the mighty Roman empire and with more cause then many rebels.

With regards to the 15 and 45 rising I cannot say I know as much as I ought, but probably Alexander Fraser because I love the tune ‘Black Bear’ which is the pipe tune of Fraser of Lovat, though it probably was not written then. However my grandfather was in the Lovatt Scouts in WW1 so it’s totally personal…

LikeLike

It can be any rebel, from any period of history 🙂

LikeLike

I’ve changed my mind about my rebel; Malala whose surname I can’t recall whose rebellion was to want education and who was shot for it. And STILL continues to fight

LikeLike

Hmm… My favourite rebel? Of the’45? Don’t know any personally, since I don’t think I was there, in a previous life or any other… As the descendant of a Scottish family (albeit borderlands) and a good Anglican Protestant, I have to take the middle way. Too many lives changed forever on either side, and the field at Culloden gives me inexplicable chills. Romantic though it may be, I can’t stand the “Skye Boat Song.”

LikeLike

Now I have good memories of it, because we used to sing it as a round at Girl Guides, which was about camaraderie, and I had no idea what it was about and could care less, because it was the first thing I ever learned to play on the guitar. My husband’s mother used to sing it to him, and he assumed it was a hymn because the man ‘born to be king’ was obviously Jesus. So there you go, so much for romance.

I get the same feeling of chills at Naseby; I’ve never been to Culloden.

LikeLike

My favourite rebel? James Augustus Whitley who, as a teenager, was employed as the prompter’s assistant in a theatre in Dublin. He stole the prompt books and ran away to join up with a beautiful widowed actress, married her, moved to England and became the greatest provincial theatre manager in 18thc England. He waited until the Pretender was long gone before he took his company of comedians to Derby, though.

LikeLike

I thought I ought to put in a word for a Chesterfield man who was involved in Peterloo – John Thacker Saxton. He was a radical from a very loyal English town (we had held French POWs here) and his father was sometime Mayor of Chesterfield. John Thacker Saxton was still campaigning for parliamentary reform in the early 1830s in Hertford.

LikeLike

good man

LikeLike

The feminist writer Mary Wollstonecraft. She was a true radical and rebel who campaigned for the rights of women years before the formation of the women’s suffrage movement.

LikeLike

Lord Byron, rebellious, witty and shocking in his published works, such as Don Juan. Fighting for Italian and Greek independance. Supporting radical causes in his parliamentary speeches and being such an interesting character that he can still shock today.

LikeLike

Robin Hood would be my choice, although not entirely sure he was that honorable.

LikeLike

Rebels are prevelant throughout history, but my fave has to be Thomas Becket, not because it got him killed, but because he stuck by his decisions xx

LikeLike

So many to choose!

For me, it must be Elizabeth I. For a queen, yet an English Queen, to choose not to marry was an incredibly rebellious choice for herself and for her country. She chose not to allie the country with Spain, enormously powerful at that time. In staying unmarried she remained uncompromised, politically, in terms of religion and in leadership.

Best regards

LikeLike

I have picked Oskar Schindler who saved so many people quietly and steadily throughout WW2,despite the huge personal risk to himself and his family.He stood by what he believed in, whilst others toed the official line to save their skins and line their pockets

LikeLike

Beatrix Potter, not just for her publishing career but also for her ecology work in the Lake District (before it was fashionable). She achieved all this in a patriarchal society.

LikeLike

My favourite rebel is King Richard III — he was designated a rebel by Henry Tudor (aka Henry VII), although in my view it was Henry who was the rebel, not Richard. Can you tell that I’ve read Josephine Tey’s Daughter of Time??

LikeLike

My choice of rebel would have to be Rosa Parks, who refused to give up her seat on the bus to a white passenger in Alabama, breaking the segregation law. Her brave actions and standing up for equality can be said to have launched the modern-day civil rights movement.

LikeLike

My favourite rebel at the moment is Tawakul Karman. She was the co-recipient for the 2011 Nobel Peace Prize, and has done (and hopefully will continue to do) amazing work. She is a journalist, politician, advocate for Freedom of the Press and human rights activist.

LikeLike

Has to be Robin Hood, could quite fancy living in Sherwood Foresrt with an outlaw!!!

LikeLike

Mine is Henry Hunt, Regency period radical, and orator at the mass meetings that turned into the ‘Peterloo Massacer’.

LikeLike

My favourite rebel is James Dean – just because he looked so cool! Ok – I know he wasn’t really a rebel.

LikeLike

My favourite rebel is Frankie Boyle. He doesn’t give a **** who he offends 🙂

LikeLike

My favourite rebel is Sophie Scholl, who stood up to the Nazis by distributing anti-war leaflets and in 1943 was executed for high treason with her brother Hans .

LikeLike

My favourite rebel is my great grandmother. She smuggled gold out of wartime Nazi Occupied Berlin – once getting away with it because a searcher found her false teeth rather than the loot!

LikeLike

There’s a biography waiting to be written there

LikeLike