We are delighted to welcome our guest, Naomi Clifford, host of the blog Glimpses of life, love and death in the Georgian era to recount the tragic tale of Eliza Fenning, so have your tissues handy, you’ll need them!

In the afternoon of 11 April 1815 two men came into the Pitt’s Head public house opposite the Old Bailey and seated themselves at a table. Their clothes marked them out as working men but they were clean and neat. One of them, an old man, was trying to write on a scrap of paper, but was so distressed, his hand shaking so much, that he could not manage it. His friend tried to take over, but he too could not form the letters. Eventually, the old man appealed to a stranger to help. “I want to tell the court that my daughter Eliza told me she was happy in her situation,” he said.

This simple and innocuous statement was crucial to his daughter’s fate, he said. The stranger obliged and the men left the pub and crossed over to the Old Bailey where Eliza Fenning was on trial for her life, accused of attempting to murder her employer and members of his family by putting arsenic in their dinner.

William Fenning, Eliza’s 63-year-old father, was deluded: his daughter’s short road through life had already been mapped, its course decided by a combination of personal animosity, class prejudice, conspiracy and official incompetence.

Eliza, aged 20, worked as a cook for Orlibar Turner, a law stationer living at 68 Chancery Lane, London with his wife Margaret, son Robert and daughter-in-law Charlotte. Turner also employed a maid, Sarah Peer, and two apprentices. Eliza was generally well thought-of; she was lively, amusing, amiable and hard-working. However, a few weeks before the poisoning Charlotte had threatened her with dismissal for going, inappropriately dressed, into the apprentices’ room to borrow a candle. Eliza had been upset by this and had declared to Sarah Peer that she no longer liked her mistress but seemed to put the incident behind her. In reality, it was Charlotte and Sarah who disliked Eliza.

Eliza liked cooking and wanted to show off her skill at making dumplings but Charlotte put her off. However, on 21 March, on her own initiative, Eliza asked the brewer to deliver some yeast. At this, Charlotte relented and agreed that Eliza could serve the family steak, potatoes and dumplings for dinner, and that she should also make a steak pie for the apprentices. Eliza got busy. She made the pie and prepared the dumplings. The apprentices ate at 2pm and the family at 3 so she set the dumplings by the fire to rise while she took the pie to be cooked at the bakers. When she returned she could see that the dumplings were not a success. They had failed to rise.

She must have taken remedial measures, which also failed because when she brought six dumplings to the table they were small, black and heavy. Nevertheless, the Turners ate them, as did Eliza herself. The effects were immediate. Charlotte was soon in excruciating pain and vomiting. Her husband and father-in-law – and Eliza – were also stricken. One of the apprentices, Roger Gadsden, who had picked at the dumplings in the kitchen, and later claimed in court that Eliza warned him not to do so, was also ill. Henry Ogilvy, a surgeon, was sent for, and soon there was another, John Marshall, in attendance.

Eliza asked her fellow servant Sarah Peer, who had not eaten any dumplings, to fetch her father who worked for his brother, a potato dealer, in Red Lion Street, Holborn. Sarah did not tell Mr Fenning it was urgent and said nothing about the sickness in the house, and her message slipped his mind until he was back at home. Between 9 and 10 that evening, he turned up at the Turners’ house in Chancery Lane and knocked. Now Sarah told him a barefaced lie. On the orders of her mistress, she said that Eliza was out on an errand. He went away entirely unaware that five people inside the house, including his daughter, had been poisoned. The family recovered. Whatever they had eaten had been insufficient to kill them.

Orlibar Turner seems to have immediately suspected the dumplings. Once he had recovered sufficiently he showed Mr Marshall the remains of the basin they had been prepared in. Marshall added water, stirred and decanted it and examined the sediment. He found half a teaspoon of white powder, which tarnished a knife. “I decidedly found it to be arsenic,” he later told the court. He did not detect arsenic in the remains of the yeast or in the flour.

Eliza was the only suspect, as she had made the dumplings and, still suffering the effects of the poisoning, she was taken before a magistrate and sent to Clerkenwell Prison. When her parents were finally made aware of her plight, they raised £5 for her defence. Two guineas went to Mr Alley, a defence attorney, and the remainder to a jobbing solicitor who drew up the brief. This was the sum total of her legal resources: against her were ranged the Turners and their armoury of legal contacts, favours and knowledge. The prosecution was riddled with conflict of interest: their personal friend and solicitor worked as the clerk to the magistrate who had committed Eliza.

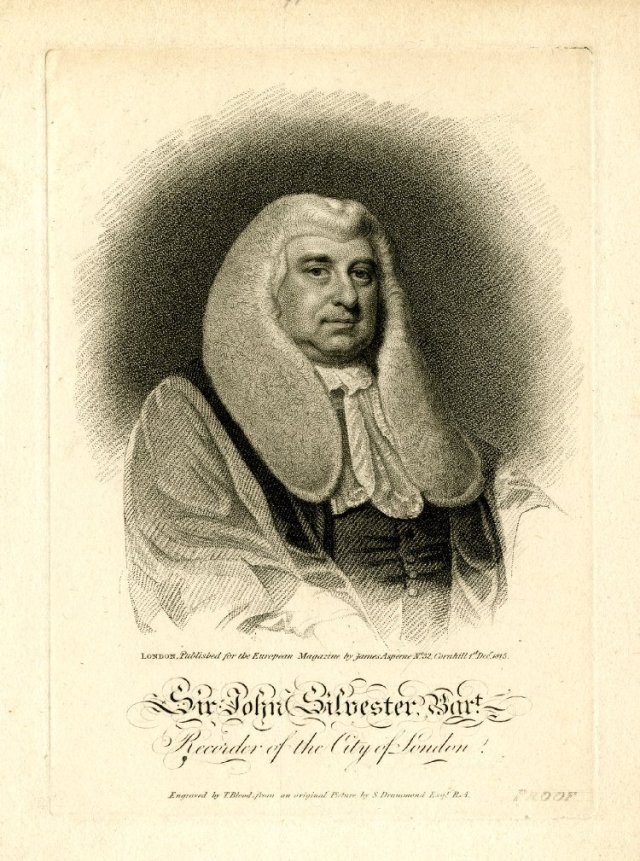

The case came to trial at the Old Bailey on 11th April 1815 and was heard by the Recorder, John Silvester.1 The case against Eliza was entirely circumstantial and focused on her general behaviour and attitude, and her potential access to the poison. Simmering with resentment at her dressing-down by Charlotte, she had stolen the arsenic and planned her murderous attack.

Orlibar Turner kept two wrappers of arsenic, tied up tight and labelled “Arsenick, Deadly Poison”, in an unlocked drawer in the office where the apprentices worked. It was used on the mice and rats who liked to eat the vellum and parchment. Two weeks before the poisoning, he noticed that it was missing. The drawer also contained scraps of paper, which the servants used for lighting the fire. During the trial, Roger Gadsden, one of the apprentices, said he had seen Eliza take paper from the drawer where the arsenic was kept. The implication was that she had seen it there and stolen it. In court Eliza said that when she needed paper for the fire she asked for it and pleaded for Thomas King, the other apprentice, to come to court to back her up. He was denied to her. Mr Ogilvy, who would have told the court that she herself had been very ill, was not called.

Eliza’s defence was feeble, to say the least. Her defence attorney Mr Alley barely spoke and was not even in court to hear the Recorder’s summing up. One of the jurymen was deaf. She was permitted to speak in her defence, but not for long. “I am truly innocent of the whole charge. I am innocent; indeed I am! I liked my place. I was very comfortable,” she said. She called five character witnesses.

William Fenning’s desperate attempt to submit sworn evidence of his daughter’s happiness with the Turners was in vain. The court would not accept his statement.

The guilty verdict and the death sentence, both predictable, were nevertheless a terrible shock, and not only to Eliza and her family. Many of the great and the good immediately started petitions: to the Home Secretary, Lord Sidmouth; to the Prince Regent. Letters were written to The Times (but not published).

Basil Montagu, a prominent Quaker, uncovered evidence that Robert Turner had had a previous episode of mental instability, appearing “wild” and “deranged”, threatening to kill his wife and himself. He sent his evidence to Silvester, who dismissed it as “wholly useless.”

An anonymous chemist decided to recreate elements of the crime himself. He made dumplings with arsenic – it had no effect on whether they rose or not. He asked his cook to make dumplings and then secretly contaminated them when she was not looking; no one noticed any change in their consistency. He even tried to convince the Turners, whose support was Eliza’s best hope of reprieve, by visiting them at home but, just as he was making headway with Orlibar Turner, John Silvester, the Recorder, entered the house and, backed by Robert Turner, convinced him not to sign the petition in support of Eliza.

The efforts of Eliza’s middle-class supporters failed. John Silvester’s hold over the case prevailed and Eliza’s execution was scheduled. She protested her innocence to the last. “The parting scene with her mother was heart-rending. They were separated from each other in a state of dreadful agony,” wrote William Hone.2

On the morning of 26 July 1815, Eliza rose at 4 am, washed and gave a lock of her hair to each of her attendants. She prayed until 7 and dressed.

“I wish to leave the world – it is all vanity and vexation of spirit. But it is a cruel thing to die innocently; yet I freely forgive every one, and die in charity with all the world, but cannot forget my injured innocence.”

She looked through the window at the other prisoners, who had been locked in their cells but who had climbed up to the windows to see her. “Good bye! good bye! to all of you,” she cried.

Dressed in white muslin gown and a muslin cap and pale lilac boots laced in front, with her arms bound, she mounted the scaffold. Before she dropped, her last words were “I am innocent!” She was followed by two others: a child rapist and a homosexual.

Amongst the 50,000-strong crowd was the writer and journalist William Hone, defender of press freedom and friend of the oppressed.

“I got into an immense crowd that carried me along with them against my will; at length, I found myself under the gallows where Eliza Fenning was to be hanged. I had the greatest horror of witnessing an execution, and of this particular execution, a young girl of whose guilt I had grave doubts. But I could not help myself; I was closely wedged in; she was brought out. I saw nothing but I heard all. I heard her protesting her innocence – I heard the prayer – I could hear no more. I stopped my ears, and knew nothing else till I found myself in the dispersing crowd, and far from that dreadful spot.”

Eliza’s parents were charged 14 shillings and sixpence for her body. They had to borrow the money. Her only possession, a Bible, was bequeathed to her mother. On 31 April she was buried at St George the Martyr, near Brunswick Square. There were a hundred mourners but many others tried to get in.

Fenning’s case continued to trouble and intrigue lawyers and scientists. Did arsenic really blacken knives? Was Marshall’s evidence true and believable? How much had collusion between the judge, the prosecutor and the witnesses been responsible for the guilty verdict and the failure of appeals for remission?

To the crowds of poor and angry Londoners, who knew that a defenceless working woman had been judicially murdered, these things were irrelevant. A thousand angry people gathered outside the Turners’ house. Some were arrested for behaving in a “riotous and tumultuous manner”. Police from Bow Street were stationed outside for days.

Commissioned by John Watkins, William Hone, who had reluctantly witnessed Eliza’s death, started gathering evidence. The Sessions Report of the trial was flawed; large sections were missing. The Important Results of an Elaborate Investigation into the Mysterious Case of Elizabeth Fenning proved Eliza’s innocence and detailed the efforts that the establishment had taken to ensure that she was executed. Silvester’s extraordinary intervention with Orlibar Turner, Basil Montagu’s doomed investigation into Robert Turner’s mental ill-health were detailed.

Hone’s publication itself became the story as Silvester, and the legal establishment tried to defend their conduct. Silvester had a reputation as a hanging judge and was biased against female defendants. There were rumours that he solicited sexual favours in return for mercy.

The Observer took the lead and its lies were repeated in newspapers across the country. The Fennings were said to be Roman Catholics, to be Irish, to have shown Eliza’s body in return for money; her father, they said, had urged her to protest her innocence only to preserve his own reputation. These allegations were printed up as handbills and pushed through letterboxes and pasted up in shop windows. John Marshall and Henry Ogilvy claimed that Eliza had refused medical treatment because she knew her plan had failed. “She would much rather die than live, as life was as no consequence to her” they said.

Even if you accept that many trials at this time were ramshackle affairs, the injustice of Eliza’s execution was a brutal shock but not a surprise. For middle-class families at a time of political change, with ideas of equality wafting across Europe, Eliza represented their greatest fear: the resentful servant with revenge on her mind.

Postscript

Orlibar Turner was declared bankrupt in 1825 (Sussex Advertiser, 7 February 1825).

In 1828, John Gordon Smith, the University of London’s first Professor of Medical Jurisprudence, noted a claim in the Morning Journal that a son of Orlibar Turner had died in Ipswich workhouse confessing that he had put arsenic in the dumplings. I can find no evidence of this but Robert Greyson Turner was certainly living in Ipswich in 1820 (his wife Charlotte was from Suffolk) – he and his brother are listed in The Poll for Members of Parliament for the Borough of Ipswich.

On 21 June 1829, The Examiner noted that William Fenning, Eliza’s heart-broken father, was still living in London. “The unfortunate girl was his favourite child.” A William Fenning died in Holborn in 1842. If this is “our” William Fenning, he would have been 91.

Endnotes

1 Fans of the BBC’s Garrow’s Law will recall Silvester as the somewhat fictionalized “baddie”. He was sometimes known as “Black Jack”.

2 The Important Results of an Elaborate Investigation into the Mysterious Case of Elizabeth Fenning.

Recommended

The Old Bailey online

Ben Wilson, The Laughter of Triumph. London, Faber and Faber, 2005 http://www.amazon.co.uk/The-Laughter-Triumph-William-Fight/dp/0571224709

William Hone, The Important Results of an Elaborate Investigation into the Mysterious Case of Elizabeth Fenning , London 1815

The Poll for the Members of Parliament of Ipswich

Header image: An Old Bailey trial in the early 19th century. From Rudolph Ackermann, The Microcosm of London (London, [1808-1810]) British Library C.194.b.305-307

I live in Ipswich and I know that the workhouse records are an unsorted hotch-potch at the moment. I’ll ask around the local historians I know to have an interest in the workhouse. It was the mental hospital for years but has been sold off under the patients, who now live in nissen-huts bereft of the wonderful grounds they once enjoyed, in a corner of the main hospital complex. [just to point out that injustice is alive and well and living in England].

LikeLike

Great story. Thank you for sharing.

Plus ça change….

LikeLike

Pingback: Merkwaardig (week 26) | www.weyerman.nl

This is such a great story, thanks for your piece. I wonder if you would mind sharing the source for the broadside image you use here? It’s such a striking image.

LikeLike

Thank you so much, we’re delighted that you found it interesting, here’s a link to the image source – http://pds.lib.harvard.edu/pds/view/4787716?n=6

LikeLike

If Eliza had really put arsenic in the meal, why serve it in such a suspect-looking dish (black, dense, unappetising dumplings) that the family would be very likely to turn their noses up against and send back? Indeed, if they had done that, it would have been a completely different story.

There can be no doubt there was a food poisoning there, but was arsenic the cause? It was never really proven. The poisoning could have been due to the dumplings turning out so horrible, the reason for which was never established. Independent experiments proved arsenic would not make dumplings turn out like that, so perhaps there was another contaminant or hygiene issues in the kitchen. I imagine kitchen hygiene standards of the period were below what they are now.

LikeLike

If I wanted to poison someone I would not serve the poison in a dish that looks unfit to eat.

LikeLike

Even for those times it sounds like a railroad. I think the people who doubted Eliza’s guilt were right. We can’t even be sure it was arsenic and not improper food handling, which is what those awful-looking dumplings point to. Those people should have picketed the biased judge’s house as they did the Turners’.

LikeLike

If Eliza served those dumplings to Gordon Ramsay he’d say something like “It looks like a f****** cannonball gave birth in there!” and throw the dumplings in the bin, if not at the wall. Eliza couldn’t have poisoned him if she tried with that dish. So why even bother with arsenic for such an unappealing dish?

And was it ever established just where that missing arsenic went to, much less it being used in the dish?

LikeLike

If arsenic was put in the dish, just how was it administered? If it was put in the dumplings, how did that white sediment turn up in the pan under test? Did some of the arsenic leach out? Even so, finding a teaspoon of it seems to stretch credibility. If it was sprinkled over after preparation, what stopped the dumplings rising and turned them black?

I don’t think any of the other suspect family members could have done it during the food preparation because Eliza was there the whole time. Could arsenic have been slipped into, say, the milk, before Eliza started cooking or got there accidentally? Arsenic was pretty much everywhere in those days, after all.

And the arsenic theft from the drawer was never linked to Eliza. Sure, she had the opportunity, but so did everyone in the household as the drawer was not locked. Pretty stupid thing anyway, keeping arsenic in an unlocked drawer.

LikeLike

Hi Mistyfan

Naomi Clifford here – I wrote the blog on poor Eliza Fenning. You make so many good points, all of which should have been presented at the trial by Eliza’s defence. Undoubtedly something happened to the Turners and they certainly ate something that disagreed with the Turners. We will never know what it was but I am currently of the opinion that it was not arsenic. I also think the Turners were actually straight up lying in their testimony, perhaps encouraged by Silvester himself, and the trial was a planned stitch-up. One of the apprentices came under suspicion, as did the Turners’ son. There are more details on the case in the chapter on Eliza in my book Women and the Gallows.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: Episode 54: The Dumplings of Death – Second Decade

Pingback: History of St George’s Gardens, Bloomsbury | Look Up London

Pingback: Horace Cotton, Ordinary of Newgate | Naomi Clifford

Pingback: The Mystery of Eliza Fenning and the Poisoned Dumplings – Kat Devitt